Collins Quotes

~ Michael Collins Quotes ~

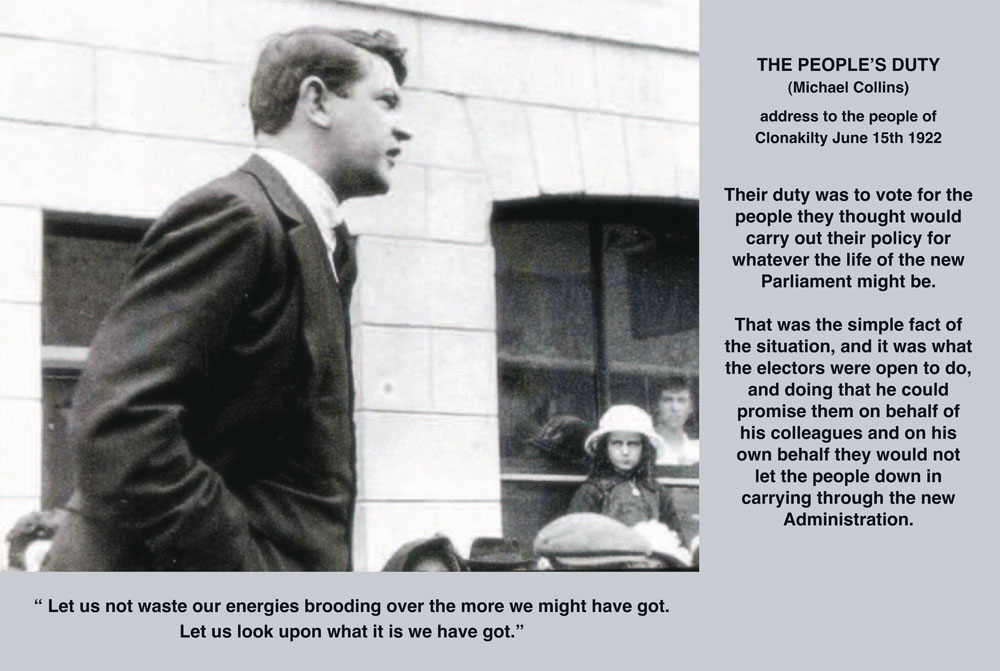

Collins’ election address Clonakilty June 15th 1922

Give us the future… We’ve had enough of your past… Give us back our country… to live in, – to grow in, – to Love. (Michael Collins)

“To me the task is a loathsome one. I go, I go in the spirit of a soldier who acts against his best judgement at the orders of his superior.” – Michael Collins on being sent to the Treaty negotiations by De Valera.

“The course of life and labour reminds me of a long journey I once took on the railway. Suddenly, there was a breakdown ahead, and passengers took the event in various ways. Some of them sat still resignedly, and never said a word. Others again, went to sleep. But some of us leaped out of that train, and ran on ahead to clear the road of all obstructions.” Michael Collins

“To go for a drink is one thing. To be driven to it is another.” – Michael Collins in a letter during the treaty negotiations.

“When you have sweated, toiled, had mad dreams, hopeless nightmares, you find yourself in London’s streets, cold and dank in the night air. Think – what have I got for Ireland? Something which she has wanted these past 700 years. Will anyone be satisfied with the bargain? Will anyone? I tell you this -early this morning I signed my own death warrant. I though at the time how odd, how ridiculous -a bullet might just as well have done the job 5 years ago.” – Michael Collins in a letter to John O’Kane after the Treaty.

“In my opinion it gives us freedom, not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire … but the freedom to achieve it.” – Michael Collins on the Treaty in debates.

“Yerra, they’ll never shoot me in my own county” – Michael Collins to Joe O’Reilly just prior to his journey to West Cork in August 1922

“That valiant effort and the martyrdoms that followed it finally awoke the sleeping spirit of Ireland” – Michael Collins, regarding the Easter Rising of 1916

“Deputies have spoken about whether dead men would approve of it, and they have spoken whether children yet unborn would approve it, but few have spoken of whether the living approve it.” – Michael Collins, Dáil debate, Christmas 1921.

“Put him in to get him out.” – Election slogan of Joseph McGuiness, in jail when elected for South Longford.

Winston Churchill on Michael Collins.

On the last occasion the two men met (recounted in ‘The World Crisis’ by Churchill) he quotes Collins as saying

“I shall not last long; my life is forfeit, but I shall do my best. After I am gone it will be easier for others.”

He described Collins thus: “He was an Irish patriot, true and fearless… When in future times the Irish Free State is not only prosperous and happy, but an active and annealing force… regard will be paid by widening circles to his life and to his death…

“Successor to a sinister inheritance, reared among fierce conditions and moving through ferocious times, he supplied those qualities of action and personality without which the foundations of Irish nationhood would not have been re-established.”

Churchill ends his chapters on Ireland by quoting Grattan:

“The Channel forbids union, the Ocean forbids separation.”

He concluded, “Two ancient races, founders in great measure of the British Empire and the United States, intermingled in a thousand ways across the world, and with the old cause of quarrel ended, must gradually try to help and not to harm each other.

“It may well be that a reward is appointed for all and that an Ireland reconciled within itself and to Great Britain will on some high occasion claim to guide the onward march and offer to the British Empire and perhaps to the English-speaking world solutions for our problems otherwise beyond our reach.”

Generous words from an Englishman, written in 1929, who knew of all of Collins’ activities from recent contact.”

“In Arthur Griffith there is a mighty force in Ireland. He has none of the wildness of some I could name. Instead there is an abundance of wisdom and an awareness of things which are Ireland.” – Michael Collins at 14 years of age.

Related Quotes

“One day he’ll be a great man. He’ll do great work for Ireland.” – Michael Collins’ Father, also named Michael, on his deathbed about his son, who was 6 at the time.

“Above average height—five foot eleven, in fact—he was powerfully built and somehow gave the impression of being much taller than he really was. He had a broad face, a jovial peasant’s face, framed by tousled dark brown hair and divided by a long, finely chiseled nose above a generous mouth. His most distinctive feature was his eyes, deep-set and wide apart. Even in repose, there was a genial, good-natured twinkle in them. When he laughed, which was often, they gave his face a crinkly effect; when he was angry, they flashed with fire and struck terror in the beholder, but within seconds they would dance and twinkle good-humouredly again. He had a frank expression and a steady, penetrating gaze which those who had something to hide would find extremely disconcerting; but most people who ever met him would fall immediately under his spell. … An immediate impression of Michael up to this time was of someone younger than his years, boyish charm is an attribute that recurs frequently in contemporary descriptions of him. … This burly, barrel-chested young man possessed a deep voice, described variously as gruff or gravelly, a bear-growl of a voice; yet it could become soft and husky when occasion demanded. It was a voice that readily betrayed the fire, the passion or the emotion of the speaker. He had the true Celtic temperament, a man who was easily moved to tears, but with the inner strength not to mind showing his feelings. For all his height and bulk, he moved with the grace of a ballet dancer. He held himself erect and strode purposefully, with a jaunty, slightly swaggering air. He had one mannerism, a toss of the head to shake back the mop of hair that fell across his brow.” James MacKay, “Michael Collins: A Life”

“…Oliver St. John Gogarty, the prominent Dublin surgeon, writer and Nationalist sympathizer…would later describe Michael as possessing ‘the quickest intellect and nerve that Ireland bred.’ For such a big man, he moved with the natural grace of a ballet dancer. Gogarty also noted that he had beautiful hands like those of a woman, and a smooth skin ‘like undiscoloured ivory.’” James MacKay, “Michael Collins: A Life”

“A tongue-lashing from Michael Collins was a terrifying experience. It cowed many, but left others sullen and resentful. Magnified in scale as well as time, this abrasive quality would make for Michael many enemies.”

“Someone with such an amount of nervous energy, who drove himself to the very limit of endurance, was a hard taskmaster to those who worked with him. He bicycled furiously round Dublin on his ancient Raleigh, charging like a whirlwind into the offices of his colleagues, or bounding up the stairs three at a time. The way Mick Collins charged around like a bull in a china shop, assessing the situation in a twinkling and barking out decisive orders, had a startling effect on subordinates. Half a century later veterans of the Anglo-Irish conflict would wryly recall the superhuman activities of the restless Adjutant-General. The word that came most readily to lips in describing him was ‘magnetic’: ‘You became aware of his presence, even when he wasn’t visible, that uncomfortable magnetism of the very air, a tingling of the nerves.’”

“He was a difficult room-mate, always first to be up early in the morning and stamping around the room disturbing the others and hauling them out of bed. All the while he would be talking animatedly, perhaps bouncing the latest ideas (which had come to him in the night) off his long-suffering bed-fellows. He had a temperament impatient of all restraint, even that imposed from within, ‘exploding in jerky gestures, oaths, jests and laughter; so vital that, like his facial expression, it evades analysis.’ Michael’s words and actions, taken separately, might be commonplace, but the vibrancy and ebullience of the man was infectious. He exuded an aura of confidence that inspired others to tackle assignments more readily; they felt safer and stronger and more fearless when he was around. Not everyone responded to his charismatic presence; there were some who considered him arrogant and insolent, stiff-necked and rude.”

“He (Michael) went to inordinate lengths to provide comforts for the Sinn Fein prisoners; he even noted the particular brands of tobacco they smoked and made sure that they got them regularly. When he could not get the brand that Austin Stack preferred he sent poor Hannie on a hunt round all the tobacconists of West London for it. On one occasion Joe O’Reilly, at Michael’s behest, asked solicitously after a sick relative of the Chief of Staff. Momentarily the adamantine mask slipped and Brugha’s eyes filled with tears. ‘Mick is so kind,’ he sobbed. ‘He thinks of everybody.’”

“Orderly in everything, he habitually used a fountain pen and abhorred a pencil. He would never use one himself and he became tetchy if anyone addressed a letter to him in pencil. What annoyed him most of all was letters signed with a rubber stamp. He ran a tight ship in his various offices and had an absolute fetish for punctuality. Woe betide the person, regardless of rank, who was a second late; Michael would greet them at the door, swinging his pocket-watch ominously in his hand and glowering furiously.”

“He invented nicknames and diminutives for friend and foe alike: Beaslai, Brugha and Mulcahy would become Piersheen, Cahileen and Dickeen, though not always to their faces. He had a genius for repartee and the stories of Michael’s witty one-liners are legion. Underneath the humour, however, there was a roughness and sometimes the comradely banter turned to merciless teasing. Joe O’Reilly was often the butt of this cruel humour, but so too was Tom Cullen. ‘Schoolboyish jokes and bubbling high spirits made him an uncomfortable companion. After a time one grew to expect nothing but the unexpected from him, in word and act.’ Late at night the tension of the day would be released in the sort of boisterous high-jinks for which he was notorious at Stafford and Frongoch (Gaols).” James MacKay, “Michael Collins: A Life”

“A sturdy, fair little boy, he took after his father in looks. Later, his hair would take the dark brown, almost black in some lights, sheen that predominates in the south of Ireland: the colour of the reed beds when the wind bends them. His eyes were grey with hazel flecks in them. The squarely-set jaw gave promise that later its owner might prove a very determined young man indeed. He laughed most of the time, flew into rages and out of them again as suddenly. If he thought anyone else had been hurt he wept bitterly.” Margery Forester, “Michael Collins: The Lost Leader”

“Mrs. (Moya Llewelyn) Davies’ first impressions of Collins were of a rather pale, heavily-built young man who smoked incessantly and was given to bombastic utterances.”

“A man who rejoiced in his own strength, of mind as of body, he could show ruthless self-control. In these early years of hard work and danger he was a heavy smoker. Suddenly he stopped. He explained to his sister Katie: ‘I was becoming a slave to cigarettes. I’ll be a slave to nothing.’”

“His favourite saint was St. Paul. ‘I know him fairly well,’ he wrote, observing that he carried a relic of that apostle of many perils in his pocket. It was no mere sharing of tribulation that attracted him to the saint, however. ‘You see he had the divine saving grace of not having been always good,’ he wrote. … Collins had always been a lover of Peter Pan; the eternal boy in himself was fascinated, perhaps even a little envious of him.” Margery Forester, “Michael Collins: The Lost Leader

The flying column’s guerilla tactics were a new from of warfare that the British refused to recognise. “Later Mao Tse Tung, Tito, General Giap, Che Guevara and Nelson Mandela were to make it respectable” – Ulick O’Connor (pg 15).

“Law and order in Ireland have given place to a bloody and brutal anarchy, in which the armed agents of the Crown violate every law in aimless and vindictive and insolent savagery.” – General Sir Hubert Gough, Commander of the Fifth Army in France, after the use of the “Black and Tans” and the Auxilliaries in Ireland.

“Michael Collins rose looking as though he were going to shoot some one, preferably himself. In all my life I have never seen so much pain and suffering in restraint.” Churchill on Michael Collins after the signing of the Treaty.

“General Collins, who appeared in uniform, is a handsome heavyset youth. He has all the charm of boyishness and much of its shyness, and gives an impression of that combination of gentleness and strength that is probably characteristic of all potentially great leaders … Though his eyes are frequently cast down he gives no suggestion of furtiveness or a lack of frankness, When he speaks one is more conscious of fluency than eloquence.” – American Senator James D. Phelan, July 1922. (taken from Michael Collins in his own words).

“Yet even the most grotesque subversions of history cannot outdistance the true facts of the story, of a country boy who became the first urban guerrilla, laid the foundations of a state and then negotiated its independence, was chairman of its Provisional Government, then commander in chief of its armed forces when it was plunged into civil war—all this before dying at the hands of his fellow republicans at the age of thirty-one.” -A.T.Q. Stewart

“Realists appealed to Collins. There would be no more glorious protests in arms, he decided. He built a cadre of realists around him, first in the IRB, then at Volunteer headquarters, where he took over Pearse’s old post as Director of Organization before becoming Director of Intelligence, finally in Dáil Eireann, as the underground government’s very effective Minister for Finance. Collins was a doer. Essentially a well-informed opportunist with very few scruples, his entire ideology could be stated in five words: ‘The Irish should govern themselves.’” Sean Cronin, “Irish Nationalism: A History of its Roots and Ideology”

“The most important of the new leaders was Michael Collins, who played a minor role in the Rising, was interned, and on release looked after ex-prisoners, thus drawing into his own hands the loose strands of what, for want of a better term, could be called ‘Irish-Ireland.’ In 1917, Michael Collins was twenty-seven years of age. He reorganized the IRB, then dominated its ruling inner circle. He had no formal education beyond primary school, had worked in the Post Office in London, was of small-farm background—a Ribbonman operating at national level. The Rising was a shock—too romantic, he told a friend” Sean Cronin, “Irish Nationalism: A History of its Roots and Ideology”

“The one thing which he could not and would not tolerate was failure, even though sound reason was given for such failure. Harry Boland, aware of this peculiar insistence of Collins’, argued that circumstances often ruled the success or failure of a particular job. ‘Not at all,’ replied Collins; ‘More often than not it is the slipshod handling of the job which brings about the failure.’ … He never dealt in theory; he had no time for it; and he refused to listen to anything which dealt only in the theoretical. He took the standpoint of a practical man whenever plans were submitted to him for approval. No one was quicker to realize that great gulf which yawned between the possible success of a theoretical plan and the more probable success of a practical plan. He was a realist, as distinct from the idealists who have numerously abounded in Ireland. It may be thought that his judgment on Padraic Pearse and the Easter Rising in general was a harsh judgment (Collins thought the Easter Rising a most inappropriate occasion for ‘memoranda couched in poetic phrases’). … Collins was a realist to the point of bluntness. It was not that he lacked the finer points of etiquette—he himself was sprung from an ancient clan; but because of the conditions in which he spent the most fruitful of his years, he exorcised everything which might hinder quick, concise thinking.”

“There was a touch of the Napoleonic in Collins’ military brilliance. He used thorough, unorthodox methods to beat his enemy, giving tactical lessons which have not been lost since his time on other guerilla fighters in many parts of the world. Being, by natural instinct, acutely aware of the possibilities attached to situations, this instinct or flair allowed of a thorough, but quick and accurate, assessment; and by this means ‘on the spot’ decisions were a matter of second nature to him. ‘I have seen him,’ remarked one of his former lieutenants, ‘do no more than push his hand through his hair; yet in that quick action the decision was made.’ A general observation that ‘Collins was forever wanting to get things done’ fits well with the restless temperament of a man who had the idea that sleep was a waste of valuable time. The driving force of the energy within him was the reason for this while stong will-power kept his nerves under full control. Mr. Moylett (an Irish businessman, and a friend of both Collins’ and Griffith’s), speaking to [Rex Taylor], recalled that Collins appeared to be quite fresh, in contrast to most others, after a debate which had lasted for eighteen hours. The tag of ‘gunman’ which became attached to his name was a title for which he had a personal loathing. Collins never killed a man in his life, except perhaps during the actual fighting operations in 1916. It was given to him, principally, by the press chiefs of Britain, who sought to glamorize a ‘wanted’ man. The events of ‘Bloody Sunday’ provided a field-day for them, and they piled on the horror. Further attempts have made in recent times to restore that old and untrue legend of ‘Collins the gunman.’” Rex Taylor, in “Michael Collins”

“That any man has greatness thrust upon him is a myth; in truth fate merely presents the opportunity while ambition and ability determine the performance. So it was with Michael Collins, the unlikely Finance Minister who proved himself an administrator par excellence.”

“When the First Dáil appointed Collins to Finance, in succession to Eoin MacNeill, a more appropriate appointee could hardly have been visualized. For despite his relative anonymity and comparatively young age—at twenty-nine he was the youngest in a cabinet whose average age was forty-four years—he discharged his duties with considerable ease, incomparable efficiency and definitive purpose during the Anglo-Irish and Civil Wars.”

“His greatest achievement in finance was undoubtedly the successful organization of the first National Loan. Yet, amongst his cabinet colleagues, Collins was facile princeps, demonstrating an administrative flair that was both meticulous and perspicacious.”

“Apart from Finance, Collins also held three other important military positions: Adjutant-General, Director of Intelligence and Director of Organisation. He conducted his military duties from offices in Bachelors Walk and Cullenswood House, Ranelagh, while his covert Brotherhood operations were directed through verbal instructions, from secret locations, usually ‘Joint no. 3’ (Vaughan’s Hotel). Because Collins was extremely well organized and efficient, he was unwilling to allow social activities [to] impinge on his work. In January 1920, for example, as the head of the London office, Art O’Brien, was visiting Dublin, Collins advised him that ‘I am so busy at present that a few hours away from my work on an ordinary day means a serious upset to me.’”

“In overall terms, Collins’ performance in Finance was outstanding by any criteria. … Collins’ personal organization skills were exceptional, allowing him to hold four major positions simultaneously, prompting him to impose order and clarity on a world of disorder and confusion. If his unexpected death robbed the state of its most capable administrator, it also denies the historian the opportunity to compare him with his successors in Finance.” Andrew McCarthy, “Michael Collins: Minister for Finance 1919-22” (in the anthology Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State)

“The characteristics which mark Collins out as a remarkably successful Director of Intelligence during the War of Independence include his evident appreciation of the importance of the collection and assessment of information as primary elements of intelligence operations which should precede action; his partial penetration of his adversary’s own intelligence system; the efficiency and ruthlessness with which action based on good intelligence was taken; and his success in preserving the security and efficiency of his own organization both in Dublin and in Britain despite the pressures it operated under because of the constant threat of raids, arrests and the capture of documents.” Eunan O’Halpin, “Collins and Intelligence: 1919-1923 From Brotherhood to Bureaucracy” (in the anthology Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State)

“‘We bend today over the grave of a man not more than thirty years of age, who took to himself the gospel of toil for Ireland, and of sacrifice for their good, and who has made himself a hero and a legend that will stand in the pages of our history with any bright page that was ever written there. Pages have been written by him in the hearts of our people that will never find a place in print. But we lived, some of us with these intimate pages; and those pages that will reach history, meagre though they be, will do good to our country and will inspire us through many a dark hour. Our weaknesses cry out to us, “Michael Collins was too brave.” Michael Collins was not too brave. Every day and every hour he lived he lived it to the full extent of that bravery which God gave to him, and it is for us to be brave as he was—brave before danger, brave before those who lie, brave even to that very great bravery that our weaknesses complained of in him'” – Richard Mulcahy in his oration at Collins’ funeral.