Michael Collins Boyhood

Michael Collins Boyhood, 1890—1906

‘A great host with whom it is not fortunate to contend, the

battle-trooped host of the O’Coileain.’

‘OLD IRISH SAYING’

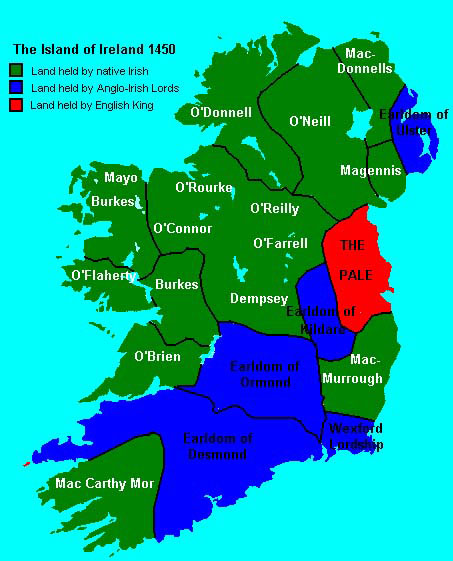

Ireland_1450

The Collins in West Cork are decended from the O’Coileain, lords of Ui Conaill Gabhra from time immemorial. Long before William the Conqueror set foot on the sister island, the O’Coileain were famed for their ferocious warrior skills. The Conqueror’s great-grandson, Henry II, received the grant of Ireland from Pope Adrian IV on condition that he brought law and order to the Irish Church and State.

Read Papal Bull of 1155 AD.

The genuineness of the Papal Bull Laudabiliter setting forth this shady deal is open to question; but the Irish, a devout race, swallowed the mandate from His Holiness and meekly submitted. The immediate occasion for the Anglo-Norman invasion, in 1170, was ostensibly the restoration of Dermot McMurrough, King of Leinster, who had been ejected four years previously. When Dermot conveniendy died and was replaced by the Norman magnate FitzGilbert, the Irish rose in revolt under Rory O’Connor, King of Connacht. King Henry himself then crossed over to Ireland on 17 October 1171, a date that would later be engraved on the mind of every Irishman. The conquest of Ireland was sudden and all-embracing; the petty kings were replaced by Norman barons and the rigours of feudalism imposed.

In one of the many uprisings of that fateful decade the O’Coileain were expelled from their lands in County Limerick (the Baronies of Upper and Lower Connelloe which includes Adare, Rathkeale & Newcastlewest.). A small remnant managed to cling on to Claoghlas (Cleanglass Townland near Newcastlewest S.S 52, 53) in the far south-west of the county till the late-eighteenth century when they were dispossessed by the Fitzgeralds. Meanwhile, the main body of the clan migrated southwards, almost as far as they could possibly go, to West Cork, one of the remotest and poorest areas in the far south-west of Ireland.

Not far from Galley Head, the promontory that separates the bays of Clonakilty and Rosscarbery, lies the straggle of cottages and farmhouses at the crossroads known as Sam’s Cross (afrer a notorious highwayman, Sam Wallace). Near this hamlet, nestling in the hills midway between the two market towns, is the tiny farm of Woodfield, ninety acres in extent, which had been rented by the Collins family for generations.

Four Alls Tavern at Sams Cross

The Four Alls Tavern

At the crossroads itself stands the Four Alls tavern which, for many years, was kept by Jeremiah Collins (and is today run by his grandson, Maurice) and still has its curious signboard inscribed ‘I Rule All, I Fight for All, I Pray for All, but I Pay for All’, captions to pictures of a king, a pikeman a priest and a farmer respectively. In a cottage across the road was born Mary Anne O’ Brien in 1855. She was scarcely out of her teens when she married one of the Collins brothers who tenanted Woodfield.

Woodfield was not untypical of the farms in this part of Ireland, with its small, stony fields on the long slope of a windswept hillside. Subdivision over the centuries had reduced it by the early-nineteenth century to a few scattered acres providing little more than subsistence farming. It was occupied by four brothers, Maurice, Thomas, Patrick and Michael John Collins. They could not afford to marry, and for years they struggled, four ageing bachelors, to make a go of the farm.

Somehow they weathered the Great Hunger of the 1840s and the upheavals of the Young Ireland rebellion in 1848, and were swept up in the temperance crusade of Father Mathew the following year, unreservedly accepting the supposition that strong drink was a weapon of the English squirearchy to keep the Irish docile.

In 1850 Pat and Tom, now in their fifties, had a brush with a couple of squireens who were trampling through their crops in pursuit of a fox. The Collins brothers were extremely fortunate not to be ejected from their tenancy, but for manhandling the huntsmen and driving them off their fields, Pat and Tom spent a year in Cork Gaol. Once a month Michael mounted his garron and made the fatiguing journey, through Timoleague and Bandon, to the county town twenty miles away to the north-east, bringing pathetic comfort to his gentle elder brothers whose uncharacteristic eruption had cost them so dear.

These monthly journeys to and from Cork turned Michael’s soul to iron. In the very year that Pat and Tom were convicted, an association demanding the Three Fs — Fair rent, Free sale and Fixity of tenure — was formed with the avowed intention of extinguishing landlordism altogether. Out of this association would evolve the Land League in 1879 which would eventually achieve these aims, but along the way there would be constant heartache and numerous setbacks as the Land Leaguers battled against the vested interests of the landowning classes. In the end, it would take a worldwide depression in agriculture combined with three wretched harvests in a row (1877—79) before the Westminster parliament passed the great Land Act of 1881. The youngest of the Collins brothers chafed at the seeming lack of progress towards justice for the tenantry and sought other solutions.

Michael Collins was a fervent admirer of a Rosscarbery man, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, who tried to give fresh impetus to Irish nationalism by founding the Phoenix National and Literary Society. The authorities viewed this as yet another subversive organisation and, in the wake of the 1848 uprising, it was suppressed.

Raising a family in old age must have left Michael John little time for politics. The I880s were a decade in which the Invincibles of the IRB turned to more extreme action: the murder of Lord Frederick Cavendish, Chief Secretary for Ireland, and his assistant Thomas Burke in Dublin’s Phoenix Park on 6 May 1882, was the prelude to a bombing campaign in the heart of the enemy s capital which began the following year and climaxed on 24 January 1885 with the simultaneous dynamiting of the House of Commons, the Tower of London and Vkstminster Hall. The explosions had little effect, however, and the IRB soon sank back into lethargy. The limited attainment of political objectives, mainly through the Land League founded by Michael Davitt in 1879, and the Home Rule party led by Charles Stuart Parnell, seemed to promise independence gradually by constitutional means, although it tended to polarise Ireland along sectarian lines. By 1890 the collaboration between the Liberal party led by Gladstone and the Home Rule party seemed about to bear fruit, when it was destroyed by a divorce. When Captain 0’ Shea, an Irish MP divorced his wife Kitty and cited Parnell as co-respondent, the Catholic hierarchy called for the latter’s resignation. Parnell refused and his party was violently split down the middle.

Charles Stewart Parnell

The O’Shea—Parnell scandal was coming to a head when Mary Anne was far advanced in her eighth and last pregnancy, complicated by a bad fall in which she saved the baby she was carrying but broke her ankle. The fracture was inexpertly set, leaving her with a bad limp for the rest of her days, hut she struggled on with her chores. One autumn evening she milked her cows as usual, then did a large baking and attended to other household duties before retiring to her bed where, early on the morning of Thursday, 16 October, she gave birth to her third son. Later that day, Father Peter Hill having been summoned from Rosscarbery, the newborn infant was solemnly baptised. The parish register shows that he was christened Michael, although he went through a phase in childhood where he assumed a middle name, James (after his mother’s father), and sometimes signed his name ‘M.J. Collins’, but he dropped this affectation as he got older

Mary Anne was only thirty-five, but three years had elapsed since Katie had been born. The baby’s father was now seventy-five, but his powers, both physical and intellectual, were undiminished by the passing of the years, and he would retain the appearance and vigour of a man half his age right up until his death in March 1897. The baby who bore his name became the favourite child of Michael’s last years. Young Michael, in turn, was very close to his elderly father and when he was very young would accompany him everywhere and in his own childish way try to help about the farm.

The young Michael Collins with his mother Mary Anne, his Grandmother, Sister and brother Johnie

Life at Woodfield in the 1890s must have been idyllic. Mary Anne doted on her youngest, and the boy’s sisters adored him unreservedly; ‘We thought he had been invented for our special edification,’ commented Hannie Collins many years later. Little Michael grew up in a close, loving environment. It would not have been surprising had all this love and attention turned his head, but he seems to have gained the positive benefit of self-assurance without the negative quality of becoming self-centred. His earliest memories were of his parents and his sisters, of cuddling up to his mother as she milked the cows and softly crooned the Irish ballads which she had learned from her grandmother. It was Michael’s earliest exposure to the Irish language; years later he would regret that he had not had the opportunity to speak it as a native.

Old Michael John appears to have been a rather austere, forbidding figure, awkward and reserved with his older children; but young Michael’s perception of him was quite different. In extreme old age Michael opened out to his last-born, whom he regaled with the myths and legends of old, as well as exciting deeds and tragic tales from Ireland’s history.

Running like a golden thread through this oral education was the rank injustice of the antiquated system of landholding. Some day this must be put right, and the land restored to the people who actually tilled the soil. In fact, the Land Purchase Act of 1885 made it practicable for tenants to buy their farms. The landlord would receive eighteen times the annual rental from the government, and the tenant would repay this sum over forty-nine years. Later legislation would accelerate the process by providing generous bonuses (up to an eighth of the purchase price). Taking advantage of this concession Johnny Collins would eventually undertake the purchase of Woodfield in 1903. By 1921, two-thirds of the land in Ireland had passed from the old landowning class to the tenantry under voluntary transactions of this kind, and one of the first acts of the Free State administration was to complete the process.

Although the worst excesses and injustice of the old land system had been mitigated by the time Michael was a little boy, the collective folk memory was sharply etched with bitter memories. As late as 1886, when Johnny was nine, he had been the tenor-stricken witness of an eviction, watching the local stalwarts of the Royal Irish Constabulary manhandling the tall gallows contraption used to batter down the mud walls of a cotter’s cabin before the thatch was torched, as the evicted family huddled shivering on a frozen November afternoon and watched their house go up in flames. Johnny never forgot the look of sullen, impotent rage on the face of the cotter. Shortly before Michael was born, an old man was forcibly evicted as he lay on his deathbed. On that occasion one of his sons was goaded into attacking the land-agent with a pitchfork, putting a tine through the man’s eye. What became of the assailant ts not recorded, but apparently there were no evictions in that area thereafter.

All this was before young Michael’s time, but he himself had a memory of ‘factor’s snash’ that would remain with him till the end of his life. On the very day he himself was killed he reminisced about an incident when he was no more than five. His father was ill at the time, and for some reason it fell to the boy to pay the rent of £4 6s 3d. On his way to the land-agent’s office in Rosscarbery, Michael chanced to see, in a shop window, a football priced at a shilling. Oh, how he longed for that football, and he quickened his step in the hope that the agent would reward him for prompt payment by giving him a shilling discount, as was sometimes the case. But the man took the frill amount, snapping nastily, ‘Tell your father he’s a fool to trust such a small lad with so much money.’ Right there and then, Michael vowed that there would be no land-agents in Ireland if he ever had his way.

In March 1897 the old man died. Michael was with him at the end and often recalled his last words: ‘I shall not see Ireland free, but in my children’s time it will come, please God.’

In adulthood Michael’s memory of his father’s appearance became hazy, but he had an instant recall of the old man’s precepts, and frequently peppered his speeches and his conversation with his sayings. Testimony as to the character of the father is abundant unflinching honesty, a rather dour integrity and a rigid set of moral principles were tempered by the essential humanity of the man. Tender feelings for those worse off than himself extended to the beasts of the field; even the rooks who nested in the trees around the litfie farmhouse were left unmolested. A concern for others would be an outstanding characteristic of Michael Collins to the end of his life, and it is idle to speculate that some of the worst excesses of the civil war, perpetrated after his death, might have been avoided.

There are also many anecdotes that illustrate his total absence of fear, even as a very small child. These stories, however, probably reflect the attitudes of the raconteur rather than revealing the truth about Michael; for an absence of fear is a dangerous quality and this, indeed, may have been ultimately his undoing. Certainly the story told by his brother Johnny, of the toddler wandering off and subsequendy being found asleep amid the straw on the floor of the stall housing a vicious stallion that only old Michael John could control, suggests foolhardiness born of ignorance. Astonishingly, litde Michael was found curled up, fast asleep, between the animal’s hooves. Another story tells how his sisters had taken him up to the loft above the living quarters, and how he fell through the trapdoor to the kitchen floor below, unscathed; but that smacks of the miraculous, rather than proving any point about Michael’s bravery or fortitude.

More important was the influence of the old man on the development of the boy’s intellect. Time and again, one sees examples of the tendency among the higher classes of society to decry the peasantry as little removed from the beasts of the field; yet there is abundant evidence in all peasant societies of the great store set upon education. This may not be an education in the formal sense of school, college or university, but it is education in its purest form, the education that springs from within. Old Michael John, born in the year of Waterloo, had grown up in an era when the Catholic peasantry was subject to harsh penal laws and social restrictions which extended to education among other things. It was left to the peasantry to redress the balance as best it could, through the system of hedge-schools, often conducted (as the name implies) in the open air.

Despite pitifully limited resources, the itinerant hedge-schoolmasters imparted an enthusiasm for learning which encouraged men and women, young and old, to carry on the process on their own. Literacy was the key to this self-education and the system, despite its primitive nature, produced an incredible number of fine scholars. Michael John had received what little formal education he possessed from Diarmuid 0 Suilleabhain, a cousin on his mother’s side, who inculcated a love of languages. As a result, Michael had a good grounding in English and French as well as classical Irish, and then went on to acquire a deep knowledge of Latin and Greek, besides the more abstruse aspects of pure mathematics. In addition to the many skills required of the small peasant farmer, who must needs turn his hand to ploughing and thatching and all aspects of animal husbandry, Michael John was adept at carpentry and cabinet making, fashioning his own furniture and constructing the doors and windows of his farmhouse or the mangers and stalls for the cattle and horses. An old man who had such a wealth of experience and an extraordinary range of skills and accomplishments, both practical and cerebral, must have been a source of wonderment to an impressionable boy. Many of Michael John’s anecdotes concerning the epic struggles of Ninety-Eight (the year in which his elder brother Patrick had been born) had the ring of truth underscored by the fact that he had got them from the lips of Diarmuid 0 Suilleabhain himself, and he, it was well known locally, had been ‘out’ in that historic year and had fought shoulder to shoulder with Wolfe Tone himself. It is hardly surprising that young Michael should develop such a keen sense of history, and a consciousness of his people’s role in it.

Michael developed into a sturdy lad, big for his age but also precocious beyond his years. From earliest childhood he had related easily to his much older brothers and sisters, to his mother and above all to his father who treated him as an equal and never spoke down to him. To this may be attributed his independent spirit; his father had taught him well, at an early age, to think for himself, to question everything. This extended into the field of religion. The Collins were devout, but this did not necessarily mean that everything about their faith was accepted unquestioningly. There is abundant evidence to suggest that Michael, in the middle period of his life, took religious observance rather lightly, but in the last three years of his life he came back to his faith and in the stressful period of the Truce and the Treaty, as well as in the civil war that followed, he often found solace in the Mass and the Rosary.

Having learned to read and write at his father’s knee, Michael was sent off to the neighbourhood school at the tender age of four and a half. The nearest establishment was the National School at Lisavaird, about two miles from the farm. Opened in 1887, it served this little community for many years but is now used as a shed for J.J. Hurley’s farm machinery business. This was a one -teacher school, catering for pupils of all ages from five to twelve. What had been so ably begun by old Michael was continued by Denis Lyons, one of those truly exceptional schoolmasters whose influence on their students lasts a lifetime. Apart from his skills as a pedagogue, Lyons had a genius for motivating his youthful charges. Ironically, the National School system had been established by the government with the express purpose of eradicating any sense of Irish nationalism from the children, and undermining any subversive notions that they might have imbibed with their mothers’ milk. Denis Lyons, however, was a seasoned veteran of the IRB who managed to conceal his Fenian sympathies from the authorities while promoting his belief in physical force, if need be, to achieve the aims of an independent Ireland. It is hard to believe that Lyons, who sailed so close to the political wind, was not detected by the board of education; but perhaps the authorities chose to turn a blind eye rather than lose a teacher of his outstanding calibre.

At any rate Michael benefited from both the fundamentals of a sound education and the subtle extracurricular activities. Many years later (in Frongoch detention camp) Michael shed some light on this. ‘ln Denis Lyons, especially his manner, although seemingly hiding what meant most to him, was this pride of Irishness which has always meant most to me.’

Another powerful influence on the young boy was James Santry. With Lyons, he was Michael’s first tutor: “capable of— because of their personalities alone — infusing into me a pride of the Irish race. Other men may have helped me along the searching path to a political goal. I may have worked hard myself in the long search, nevertheless, Denis Lyons and James Santry remain to me as my first stalwarts.”

Santry was the village blacksmith. Symbolically, his smithy was close to the school, and it was the boy’s father who brought him in contact with a man who had been his longtime comrade in the IRB. A born story-teller, Santry would often have the lad spellbound with his yarns, made all the more vivid because his father before him had forged on that very anvil the pikes which armed the insurgents in the uprisings of 1848 and 1867, while he could proudly claim that his grandfather had fought at Shannonvale in the rising of 1798.

Interestingly, Michael’s respect for Lyons was reciprocated. There is yet extant a school report in the schoolmaster’s neat handwriting, dating from 1901 when Michael was about eleven years of age:

Exceptionally intelligent in observation and at figures. A certain restlessness in temperament; Character: Good.; Able and willing to adjust himself to all circumstances. A good reader. Displays more than a normal interest in things appertaining to the welfare of his country. A youthful, but neverthe-less striking, interest in politics. Coupled with the above is a determination to become an engineer. A good sportsman, though often temperamental.

The comments on politics and engineering were bracketed with a further shrewd observation, ‘Either one of these could possibly become finalised at maturity.’ It was an assessment that would secure Michael a coveted place at the higher-grade school in Clonakilty.

Maryanne Collins had the new house at Woodfield completed in 1900. It was burned down by the Auxilieries under the command of Major Henry Wilson in April 1921.

The new house at Woodfield that Mary Annehad completed in 1900. Which was burned down by the Auxilieries under the command of Major Henry Wilson during the war of independence April 1921

After old Michael’s death, Mary Anne decided that the old farmhouse was too cramped for her large family now reaching adulthood. With remarkable singlemindedness and organisational ability — traits inherited in no small measure by her youngest son — she set about having a new house erected alongside the old, and superintended every detail down to the landscaping of a flower garden, regarded at the time as an unnecessary extravagance. The family moved in at Christmas 1900. In the new, more spacious scheme of things, Michael now had his own bedroom, with a fine window that looked north towards the hills and wooded glens of Knockfeen. The room was very sparsely furnished, from choice, the boy’s only concession to ornament being a rather sombre poem entitled ‘Moonlight in my Prison Cell’ which he framed himself with passe-partout. His sole luxury was a little bookcase containing an amazingly catholic range of reading matter. To be sure, there were books about his great heroes, Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmett, martyrs of the risings of 1798 and 1803 respectively, the writings of Thomas Davis (read again and again and leaving an indelible mark on Michael’s own political philosophy), the essays and poetry of the Sullivan brothers including ‘God Save Ireland’ which became the Fenian anthem, the patriotic novels of Banim and Kickham, O’Donovan Rossa’s autobiographical Prison Life, and many others with a strong political theme. But alongside them were the novels of Scott, Dickens and Thackeray as well as Shakespeare’s plays and the poems of Thomas Moore.

With Katie, the sister closest to him in years, Michael read The Mill on the Floss and once said to her, ‘We’re like Tom and Maggie Tulliver.’ Katie riposted that he could never be cruel like Tom, but Michael blurted out, after a hesitant pause, ‘I could be worse.’ This seemingly casual remark remained sharply etched in his sister’s mind. Years later, when the horrible deeds on both sides in the civil war were made known, she would ponder on Michael’s words. Did he, perhaps, have some premonition of the ruthlessness which, though devoid of cruelty, circumstances would force on him? If so, she took some comfort from the fact that he died when he did, before the worst excesses were perpetrated and tarnished the reputation of his contemporaries.

At the turn of the century this very close-knit family began to drift apart. First to go was Hannie, who secured a clerical post in the Post Office Savings Bank in London in March 1899. This was inevitable, for Woodfield could not provide work for everyone, and it was always assumed that some at least — the brighter, more energetic and more restless — would some day go forth into the world. Oddly enough, only one was drawn by that powerful magnet, America;

In 1902 Patrick departed for the New World, never to return. When Helena left home to become a novitiate in an English convent, her last sight of home was Michael running along the road after the horse and trap, waving frantically until he was swallowed up in the dusty haze. Johnny would remain to work the farm, and suffer grievously during the Troubles when the Black and Tans burned down the farmhouse as a reprisal against Woodfield’s most notorious son. Until the late-1980s the house that Mary Anne erected with so much care was a grassy ruin, a stark reminder of these terrible times. As the centenary of the birth of Michael Collins approached, however, the ruins were tidied up and gardens laid out to form the Michael Collins Memorial Centre, inaugurated in October 1990.

Margaret married Patrick O’Driscoll, proprietor and chief reporter of the Clonakilty newspaper In due course they would give Michael board and lodging while he continued his studies. During this period the boy got an excellent grounding in the art of concise writing. As part-time cub reporter, he was given plenty of journalistic assignments, covering weddings, social events, football matches and the like. Having to get across the story in a limited number of words would prove an excellent training. The terse, matter-of -factness of local journalism never left him, and would be the hallmark of the reports and directives issued during the years of conflict.

One thing appears to be lacking from Michael’s early boyhood; he seems not to have had any close friends of his own age. After his father died, he preferred his own company, often going for long solitary walks through the beautiful, wild countryside.

Sometimes he would carry a book with him, usually Davis, which he read and reread, ruminating over its precepts: education, knowledge, toleration, unity, self-reliance, all fused by love of country. This was the Davis recipe for a sovereign Ireland in which Nationalist and Unionist, Catholic and Protestant would sink their differences and work together for the common good. These were ideals which made a lasting impression on Arthur Griffith, twenty years Michael’s senior and already making a name for himself And, in turn, Griffith attracted the attention of the precocious schoolboy. In an essay written at the age of twelve, Michael extolled his new-found hero:

“In Arthur Griffith there is a mighty force afoot in Ireland. He has none of the wildness of some I could name. Instead there is an abundance of wisdom and an awareness of things which ARE Ireland”.

This is all the more remarkable because, at that time, Griffith’s potential was recognised by very few politicians. The star of John Redmond, leader of the revitalised Irish Parliamentary Party, was then in the ascendant . By 1902, when Michael penned this essay, Griffith had been out of active politics for more than a decade, a victim of the scandal that destroyed the Parnellite faction.

After Parnell’s death in 1891, Griffith turned instead to the cultural renaiscence of Ireland and threw himself wholeheartedly into the Young Ireland League, the Celtic Literary Society and the Gaelic League which strove to save the native language from extinction. At the turn of the century he founded Cumann na nGaedheal, a federation of patriotic youth clubs of various hues and aims whose common factor was their detestation of the Irish Parliamentary Party led by John Redmond. In the same essay Michael expressed himself trenchantly against the Redmondites as ‘Slaves of England’ and ‘chains around Irish necks’.

There was no point in merely deploring the self-serving policies of the Irish Parliamentary Party; it was necessary to come up with a viable alternative. With such stalwarts as Maud Gonne and WB. Yeats working for Cumann na nGaedheal, Griffith could call on some of the sharpest intellects of the period in developing his political ideas. Behind Cumann na nGaedheal, moreover, was the IRB which imparted the separatist complexion of the movement.

These strands became entwined in 1905 when Griffith formed a new political party whose name in Irish literally meant ‘We Ourselves’, though it is often translated as ‘Ourselves Alone’. The party was Sinn Fein.

While these political developments which would have such long-term repercussions on Ireland were in the making, Michael was attending classes at the National School in Clonakilty (now the West Cork Museum). At Lisavaird Michael had been head and shoulders above his peers; in Clonakilty he faced much stiffer competition, but by the end of his first term he had found his feet and was consistently at the top of his class. Mary Anne, now in her late forties and in poor health, feared for the future of her brilliant but erratic son. ‘I am afraid he will get into mischief,’ she confided in one of her daughtcrs, perhaps with some premonition of the dangerous years ahead. Mary Anne was anxious that Michael should follow in Hannie’s footsteps and pass the all-important Civil Service examination that would give him a job for life and a good pension at the end of his career.

The headteacher, John Crowley, concurred. At the age of fourteen Michael was weaned away from any residual notions he may have had about becoming an engineer and put into Crowley’s special class which he coached relentlessly for the Civil Service examination. There were very few options. With a good pass in the school certificate examinations Michael could hope for little opportunity locally beyond recruitment into the Royal Irish Constabulary (a prospect which he found distasteful).

So he gave way to his ailing mother’s wishes and diligently studied for the Civil Service examination, sister Margaret keeping an eye on him. The only break from his studies came on Saturday mornings when he would set off along the winding country road, skirting the Curragh Lough, and down to the gleaming cottages of Sam’s Cross and the welcoming farmhouse beyond.

In 1904 he acquired his first bicycle. Little did he realise, as he cycled along the country lanes exploring the hauntingly beautiful countryside on the south coast, that the day was not far off when he would wage war on the mighty British Empire — from the saddle of a bicycle.

Apart from intellectual pursuits, Michael, who was even then above average height and broad of frame, excelled at all manner of individual sports but had little real aptitude for team games in which his fiery temper often led to a punch-up on the field. He was exceptionally strong and well built, energetic and enjoyed the rudest of health. Among his favourite sports were wrestling, running, jumping and horse-riding. Sean Deasey, a contemporary at Clonakilty, later recalled that his classmate was ‘powerful in figure for his age, and a veritable terror at the sport of wrestling’.

Katie was the nearest thing to a boon companion at this period, and they would often go for long bike rides together at weekends; but in his last year in school Michael formed a close friendship with Sean Hurley, whose family background was very similar. In the summer vacation they stayed turn about in each other’s homes, wrestling, cycling and working in the fields together. What attracted them to each other was primarily kinship — they were second cousins but they also had a very similar political outlook.

Both boys dreamed passionately of an independent Ireland, but Sean was the more realistic, down-to-earth of the two, whereas Michael’s optimism for the future was unbounded. Years later Sean would recall the day that they cyded past the house occupied by a landlord who had earned a reputation in bygone years for heartlessly turning out his tenants. Michael cried out vehemently, ‘When I’m a man we’ll have him and his kind out of Ireland!”

Late in 1905 Michael passed the Civil Service examination with flying colours and in due course received notification that he had been appointed to a clerkship in the Second Division at an annual salary of £35.”

He had the choice of several government departments but he opted for the Post Office Savings Bank, where his sister Hannie was already established. He completed the school term at Clonakilty and in July 1906 prepared to leave the little world of West Cork for the excitement and uncertainties of London. Before he left home, he tramped round the lanes and fields that he had known all his life. Now, on these beautiful summer days, he began to see the old familiar places through new eyes. He was leaving, perhaps for ever.