Irish Civil War

~ The Irish Civil War 1922-1923 ~

A paper delivered to NYMAS

at the CUNY Graduate Center,

New York, N.Y.

on 11 December 1998.

Paul V. Walsh

3412 Huey Ave

Drexel Hill,PA. 19026-2311

PVWalsh1014@aol.com

THE IRISH CIVIL WAR

1922-1923

A MILITARY STUDY OF THE CONVENTIONAL PHASE

, 28 JUNE – 11 AUGUST, 1922.

The Irish Civil War was one of the many conflicts that followed in the wake of the First World War. By the standards of the ‘Great War’ it was very small indeed; roughly 3,000 deaths were inflicted over a period of eleven months, probably less than the average casualties suffered on the Western Front during a quiet week.(1) However, wars should not be judged solely by the ‘Butcher’s Bill’. The Civil War contributed directly to the character of Ireland and Anglo-Irish relations, creating patterns that have only begun to be challenged in the past thirty years. As with all civil wars, this conflict generated extremes of bitterness that have haunted public and political life in Ireland up to the present day. Indeed, it is only after the passage of seventy-five years that scholars are able to approach the subject of the Civil War with some degree of detachment. Significantly the two main political parties in Ireland, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, are the direct descendants of the opposing sides of the war. Although partition was an established fact at the beginning of the war, the conflict in the South only served to further undermine any possibility of reunification. Thus the Civil War is one of the factors that has contributed to the thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland which only now may be in the process of being resolved.(2) For our purposes, the military significance of the Irish Civil War is that it witnessed the birth of the Irish Defence Forces, an army that has distinguished itself outside of its homeland through extensive service in various U.N. Peacekeeping operations.(3) Conversely, it was also a decisive turning point in the history of the Irish Republican Army (I.R.A.). (4) The Civil War was the only conflict in Ireland during the twentieth-century that involved an extended period of conventional fighting and, while it certainly did not serve as a model for innovation, the conduct of the war by both sides at least reflected a number of important military trends that would decisively shape operations in the Second World War. Although this paper will focus on the military aspects of the war, consideration must first be given to the complex political aspects that led to the outbreak of the war and provided the motivations of the opposing sides.

THE SEEDS OF CIVIL WAR ARE PLANTED

On 11 July, 1921, a Truce came into effect ending the Irish War of Independence which had lasted for over thirty months. (5) While the war had succeeded in forcing the British to the negotiating table, it had also exposed serious divisions within the nationalist movement, divisions that would only be exacerbated by the efforts to reach a lasting peace with Great Britain. The war had begun in the wake of the overwhelming success in the general election of December 1918 of ‘Sinn Fein’, the nationalist political party founded by Arthur Griffith. Following party policy, the Sinn Fein candidates who had been elected to parliament in London abstained from attending and, instead, formed their own legislative body, known as the ‘Dail Eireann’, headed by Eamonn de Valera as President. The Dail ratified the declaration of a Republic made during the 1916 Easter Rebellion and sent a delegation to the Paris Peace Conference to obtain support for Irish independence. (6) However, the I.R.A, which was nominally subordinate to the Dail, initiated their own efforts to win independence through military means without bothering to consult the Dail, efforts that began the war with Britain in January, 1919.

Nothing could better illustrate the different philosophies of the opposing traditions that made up the movement for independence in modern Irish history than these divided efforts. Essentially the struggle for independence had been pursued through two opposite, often antagonistic, traditions; the ‘Constitutional Tradition’, which sought to use peaceful political means, and the ‘Physical Force Tradition’ which sought to win freedom through military action. (7) The Civil War would largely be a struggle between these opposing traditions. During the war British authorities banned the Dail. This only served to place greater power in the hands of the leaders of the I.R.A. (8) As the Minister of Propaganda, Desmond Fitzgerald, observed, “In the late war against the British we had to put more or less unlimited powers into the hands of our soldiers.” (9) The weakness of the Dail generated contempt within the I.R.A for the politicians in Dublin. Chief of Staff Gen. Richard Mulcahy complained that: ”No single Government Department has been the slightest assistance to the army and some of them have been a serious drag… The Army can no longer afford to dissipate any of its energy bolstering up Civil Government without getting a return in kind. The plain fact is that our civil services have simply played at governing a Republic, while the soldiers have not played at dying for it.” (10) Just as the I.R.A. was critical of the Dail, the units in the field were critical of the G.H.Q. The nature of a guerrilla war waged by a clandestine force in a rugged country such as Ireland led inevitably to the remoteness and independence of local I.R.A. units from the G.H.Q. in Dublin. (11) As Ernie O’Malley, Commander of the 2nd Southern Division, noted, “G.H.Q. issued general instructions, but our operations were our own.” Liam Lynch, Commander of the 1st Southern Division, was less charitable; “[G.H.Q.] showed all-round inefficiency, and gave very little help to the country.” (12) These antagonisms would have serious consequences following the conclusion of the war with Britain. The actual fighting in the war was for the most part limited to the southern province of Munster and Dublin city.

Local commanders within these areas believed the war was following a generally successful course. By contrast G.H.Q., headed by the Director of Intelligence, Michael Collins, viewed the efforts of both the I.R.A. and its British opponents in their totality, so that it was only too aware of the army’s limitations. As Chief-of-Staff Gen. Richard Mulcahy was to point out in the Dail, far from being able to drive the British from Ireland, by the end of the war the I.R.A. was incapable of driving the British out of a, “fairly good-sized police barracks.” (13) The author Michael Hopkinson has concluded, “At best the I.R.A. achieved a military stalemate which prevented the British from administering the south and the west.” (14) Not surprisingly when the Truce was announced on 11 July, 1921, it was interpreted differently by the various commands in the I.R.A. Those in the more active areas assumed that it was simply a means of achieving a breathing space, after which the war would be resumed. (15) De Valera began preliminary negotiations for Irish independence with Prime Minister Lloyd George almost immediately after the Truce, but the British quickly established two preconditions for formal negotiations: they would yield no more than Dominion status to Southern Ireland, which included a declaration of loyalty to the Crown, and the North could only be incorporated by voluntary means. This latter pre-condition simply recognized the state of partition that had already been established by the Government of Ireland Act of 1920, which gave Northern Ireland its own parliament, which met for the first time on 22 June, 1921. (16) With the approach of formal negotiations to draw up an Anglo-Irish Treaty, De Valera decided to remain with the Dail in Dublin and, in his place, appointed a delegation of five members, headed by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith. His insistence that any settlement should be referred back to the Dail before it was signed was contradicted by his bestowal of full plenipotentiary powers on the delegation. Negotiations lasted from 11 October until the final day of 5 December without producing a settlement acceptable to both sides. (17) Under pressure from his own party, Lloyd George presented the Irish delegates with an ultimatum; sign the Treaty as it existed or face the renewal of ‘immediate and terrible war’. (18) They were given two hours to decide. Collins and Griffith concluded that, regardless of the inevitable opposition of the Dail Cabinet under De Valera and the I.R.A., the Treaty was the best that could be obtained from Britain at that time and that it was likely to receive the support of the Irish people. Thus they exercised their plenipotentiary powers without consulting Dublin.

De Valera was taken by surprise when the delegation returned with the Treaty, though he believed it would be defeated in the Dail Cabinet. Contrary to his expectations, however, it passed through the Cabinet into the full Dail. Three weeks of bitter debates followed. The supporters of the Treaty revealed varied motives: Griffith believed it was an acceptable settlement for Ireland, while Collins viewed it as a useful first step from which further freedom could be achieved. In general, however, supporters of the Treaty offered pragmatic justifications for its acceptance. Collins, who was impatient with legal technicalities, stated that the removal of , “[British] military strength gives the chief proof that our national liberties are established.” (19) Those who opposed the treaty believed its compromise of accepting Dominion status and partition betrayed the ideal of an independent Republic for which the War of Independence had been fought. (20) Liam Mellows declared angrily, “The delegates…had no power to sign away the rights of Ireland and the Irish Republic.” (21) On 7 January, 1922, the Treaty was ratified by a margin of only seven votes. (22) The Treaty not only split the Dail, but the party of Sinn Fein and the I.R.A. as well. (23)Ironically, the most publicly outspoken critic of the Treaty, De Valera, was in reality the least important (all the more so when, at the head of the opponents of the Treaty, he left the Dail in protest three days after its ratification). Rather, it was the rejection of the Treaty by the majority of the I.R.A. that threatened the outbreak of civil war.

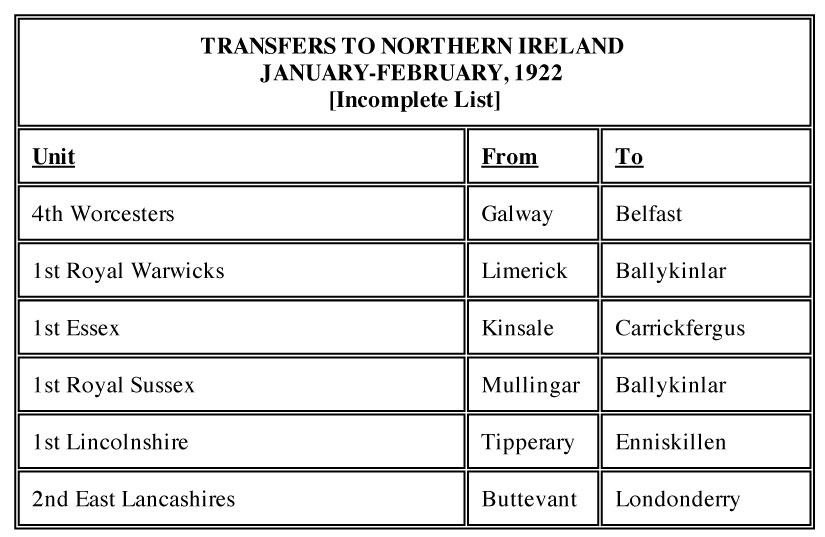

While De Valera publicly supported I.R.A. leaders who opposed the Treaty, he was at heart a Constitutionalist and opposed any suggestion of a military solution. (24) For their part, the anti-Treaty leaders within the I.R.A., consistent with their attitudes during the War of Independence, were dismissive of politicians in general. Liam Lynch, the O/C of the 1st Southern Division, remarked, “The army has to hew the way to freedom for politics to follow.” (25) The comments of the Director of Engineers, Rory O’Connor, were more provocative. At a press conference on 22 March, when asked if there was to be a military dictatorship, he replied, “you can take it that way if you like”, further stating, “There were many times when revolution was justified and the Army had to overthrow the Government….” (26) No one in the I.R.A. appeared to be aware of the inherent contradiction of furthering the cause of a Republic through the establishment of a military dictatorship. (27) Turning to their tradition of serving their own elected body, a tradition that had proceeded the existance of the Dail, the commanders of the I.R.A. who opposed the Treaty held a convention in late-March at which they formed an Army Executive and repudiated their allegiance to the Dail and G.H.Q. (28) In turn, G.H.Q. declared that those commanders who attended the convention would no longer receive support of any kind for their units, forcing them to live off the land at the expense of the people in their districts. (29) As the author Michael Hopkinson observed, “Thanks to the association of anti-Treaty units with commandeering, looting, censorship and compulsory levies, the Provisional Government was increasingly able to use the virtues of majority rule and law and order as major planks.” (30) The Provisional Government mentioned above was formed in January, 1922, according to the terms of the Treaty to act as a transitional body that would oversee the creation of the new state, to be known as the Irish Free State. (31) Needless to say, the opponents of the Treaty did not recognize the authority of the Provisional Government. The most direct challenge to that authority came on 13 April when the Army Executive ordered anti-Treaty units to occupy the center of the justice system in Ireland, the massive Four Courts building in Dublin. (32) Despite such provocations and other crises brought on by opposing units attempting to occupy barracks throughout the country that were being evacuated by the British, six months passed between the signing of the Treaty and the outbreak of the Civil War (see Appendices A and B). (33) This was a reflection of the sincere reluctance of former comrades in arms to come to blows.

Every avenue of compromise was explored and on 20 May a solution appeared to have been found when a pact was signed by Collins and De Valera. But the constitution for the new Irish Free State that came out of the ‘Collins-De Valera Pact’ contradicted the terms of the Treaty, so that, upon meeting with the British Government, Griffith and Collins were forced to accept an amended version that was stripped of the compromises upon which the pact was founded. (34) The amended constitution was published on 16 June, the day in which a general election was held to determine the composition of the new Dail of the Irish Free State. The election was seen by everyone as a referendum on the Treaty issue. Fifty-eight Sinn Fein supporters of the Treaty were elected compared to thirty-six Sinn Fein opponents of the Treaty. In addition, the thirty-four non-Sinn Fein candidates were elected from parties, such as Labour and Farmers, that also favored the Treaty. The results of the election bestowed legitimate democratic authority upon both the Provisional Government and the Irish Free State, which was scheduled to be established on 6 December. (35) Shortly after the general election the events that would force the outbreak of war began in London.

On 22 June Gen. Sir Henry Wilson, the security advisor for the new state of Northern Ireland, was shot dead by two I.R.A. men outside his home. Although evidence pointed to Collins’ involvement, the British government chose to use the incident as an excuse to demand action from the Irish government against those who opposed the Treaty, specifically the men in the Four Courts. (36) Initially Collins told the British Government that they could do their own ‘dirty work’ and Gen. Nevil Macready, C-in-C of British Forces in Ireland, was ordered to attack the Four Courts on 25 June (see Appendix C). Fortunately for the supporters of the Treaty on both sides of the Irish Sea, Gen. Macready backed down at the eleventh hour. But it was now clear that the British would not remain patient for long. Collins had always supported the Treaty as a means of achieving the removal of British troops. Now the opponents of the Treaty threatened to keep them from leaving, either because they would be used to eliminate their presence in the Four Courts, which would re-ignite the war between Britain and Ireland, or through provocation on their own by attacking British troops, which would produce the same results. (37) Griffith and the other politicians had wanted to act against the anti-Treaty I.R.A. as far back as March, but they were forced to wait for the loyal military to build up its strength. (38) Now the Provisional Government not only had a popular mandate from the electorate, but the anti-Treaty forces had provided it with two further advantages. On 18 of June, during a meeting of the Army Executive, a disagreement arose between the anti-Treaty leaders in the Four Courts and those outside of Dublin, causing a temporary split that isolated the Four Courts garrison. (39) Although Collins had probably come to a decision over whether to attack the Four Courts by 26 June, the leaders there handed him an excuse that served to mask the pressure from London when, in retaliation for the arrest of one of their officers, they kidnapped the popular Assistant-Chief-of-Staff, J.J. ‘Ginger’ O’Connell on 27 June. (40) That same night troops loyal to the government were ordered to take up positions around the Four Courts. Following the failure to respond to an ultimatum to evacuate the building, artillery opened fire on the Four Courts, beginning the Irish Civil War at 4:15 Am. on 28 June.

THE OPPOSING FORCES OF THE CIVIL WAR.

THE ISSUE OF NAMES: A variety of names were applied to the opposing sides in the Civil War, both during the war and in subsequent writings. Those members of the I.R.A. who opposed the Treaty were referred to as ‘Rebels’, ‘Mutineers’, ‘Die-Hards’, ‘Republicans’, ‘Executive Forces’ (after the Army Executive) and ‘Rory O’Connor’s Men’ (after the leader of the faction in the Four Courts). Maj.Gen. Piaras Beaslai, director of the Provisional Government’s propaganda, is credited with coining the term ‘Irregulars’ for the anti-Treaty I.R.A. The troops that fought in support of the Treaty were referred to as ‘Provisional Government Forces’, ‘National Forces’, ‘Regulars’, and ‘Free Staters’ or ‘Staters’ for short. In this paper the opponents of the Treaty are referred to as ‘Republicans’, while the supporters of the Treaty are referred to as ‘Free State Forces’ or ‘Government Forces’ (even though the Free State was not officially established until 6 December, 1922). (41)

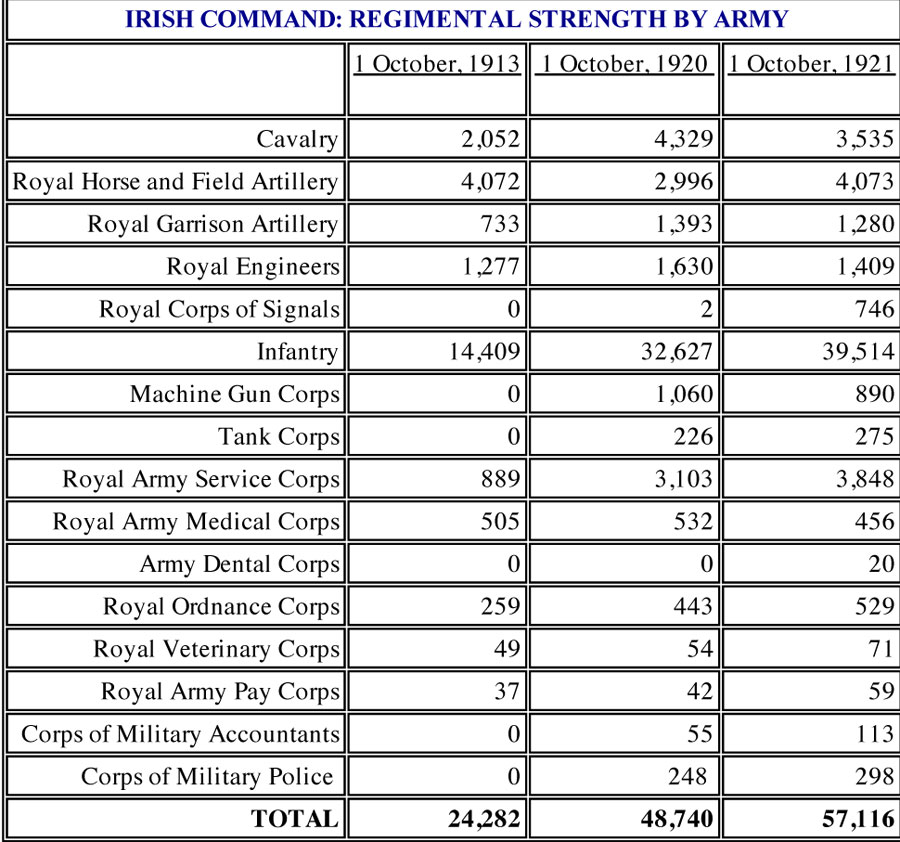

The military situation at the outbreak of the Civil War did not appear to favor the Free State.(42) Although roughly seven out of a total of sixteen I.R.A. divisions remained loyal to the G.H.Q., the size of these units varied enormously. The two largest divisions for instance, the 1st and 2nd Southern under two staunch Republicans, Liam Lynch and Earnie O’Malley respectively, contained a third of the I.R.A.’s total force (see Appendices D and G). In sheer numbers, the Free State Army was outnumbered by odds of more than two to one. (43)Moreover, the majority of the most active units of the War of Independence and, thus, the most experienced troops, supported the cause of the Republic. (44) In terms of deployment, Republican forces dominated the provinces of Ulster, Connacht, and Munster; three-quarters of the country. Although Free State forces were predominant in the province of Leinster, the majority of the troops in the Dublin Brigades were Republican. If the government lost the capital, the Republicans would have won the war in a single stroke.

But while the potential for a Republican victory existed, highly motivated commanders who were united in their efforts allowed the Free State to seize the initiative (see Appendices Hand I). (45) Even before the attack on the Four Courts, Ernie O’Malley lamented the lack of unity among the Republican high command, stating, “There was no attempt to define a clear-cut policy. Words ran into phrases, sentences followed sentences… A drifting policy discussed endlessly in a shipwrecked way.” (46) Although Florrie O’Donoghue of the 1st Cork Brigade was certainly correct when he declared, “Despite six months of talk of the possibility of civil war…no plans existed on either side for conducting it.”, it was the military leadership of the Free State that reacted first to the outbreak of war and reacted decisively.(47) The old advantages of the I.R.A. in the War of Independence were largely nullified during the Civil War. Popular support was not as forthcoming, as Harry Boland, Republican Director of Operations, lamented, “There is no doubt that the people in the main is [sic] against us at present, believing that we are to blame for the present state of affairs.” (48) The need for Republican units to commandeer supplies and their strategy of disrupting communications further alienated their cause from the general public. When the Republicans fell back on a guerrilla strategy, the secrecy that had preserved them during the war with Britain was undermined by former comrades in arms who knew the identity of enemy officers and men, and the location of their hideouts. (49) The I.R.A. formed the basis for the armies of the opposing sides during the war.

Although its membership was quite large, only a fraction of these were veterans of the full-time Active Service Units (A.S.U., also known as ‘Flying Columns’) that had done most of the fighting in the war with Britain. (50) In addition, a large number had joined following the Truce, and were derisively known as ‘Trucileers’. (51) Because the Free State forces were seriously outnumbered, they began recruiting even before the outbreak of the war.

Their most reliable unit, which would help decide the contest in Dublin and provide shock troops for operations throughout the country, was the ‘Dublin Guard’. It originated from the Dublin city A.S.U. – fifty men under Paddy O’Daly – which had worked closely with Collins. When the Guard took possession of Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin on 1 February, they were a Company sized unit. By May they had expanded to the size of a Brigade. (52) With the Dublin Guard and those I.R.A. units in the field who supported the Free State serving as a foundation, the government sought to expand the Army following the outbreak of the war.

On 3 July a force of 20,000 men was authorized, recruits being required to enlist for six months of service. The number was raised in August to 35,000. (53) By the end of the war, the Free State Army had grown to roughly 55,500 men and 3,500 officers. (54) The Free State sought to make up for a lack of experienced personnel by recruiting veterans of the British Armed Forces (or any other armed forces, for that matter; Generals J.J. ‘Ginger’ O’Connell and John Prout had both served in the U.S. Army). (55) The army was in need of specialists in particular: drill instructors, pilots, and anyone with logistical, legal, or medical experience. The Republicans, who themselves had used British Army veterans as drill instructors, accused the Free State of recruiting from the infamous ‘Black-and-Tans’. In fact, very few of the men that joined the Free State Army had served in the war against the I.R.A., much less with the ‘Black-and-Tans’. (56) Nevertheless, with such an enormous influx of personnel, an individual’s character was not an issue. At the Army Enquiry of 1924, Gen. Richard Mulcahy stated, “Old soldiers, experienced in every kind of military wrong-doing, were placed under the command of officers necessarily inexperienced and the resulting state of discipline is not to be wondered at.” (57) Discipline was a problem in both armies, and was exacerbated by the freedom exercised by local I.R.A. commanders on both sides. James Hogan, Free State Director of Intelligence, explained, “The Irish Army started on a territorial basis like feudal armies, and the feudal and baronial mentality is by no means dead in this country…To give undue powers to individuals or Commands is to feed and stimulate such instincts.” (58)

Discipline was further threatened by the conflicting motives and loyalties of the opposing troops. When the war broke out, many I.R.A. members joined one side or the other merely on the basis of which group of comrades they happened to run into first. Personal loyalties often played a more important role than ideology, as suggested by the close ties of the Dublin Guards with Michael Collins. (59) ‘The Big Fella’s’ charismatic personality was a critical factor in retaining the allegiance of many I.R.A. commanders and their units, which is one of the reasons why he took up the position of C-in-C of the Army. (60) On the other hand, many if not most of the wartime Free State recruits joined the army to escape widespread unemployment, which was further aggravated in Ireland by the Civil War itself. (61) In any case, allegiances remained uncertain throughout the war. It was not uncommon for units to switch sides and mutinies to break out. Indeed, the attack on the Four Courts was delayed when a group of forty Free State troops mutinied. (62) While most mutinies broke out over the issue of back pay, the Republicans made a conscious effort to infiltrate the Free State Army and foment unrest. (63) Adjutant General Georoid O’Sullivan commented, “At the time we were in Beggar’s Bush I did not know but the man in the next office would blow me up…”(64) Because loyalties were confused, men on both sides were initially reluctant to fire on old comrades. (65) By the end of the war, however, acts, official or otherwise, were being committed by both sides that would have been unthinkable at its outbreak.

The opposing armies began the war only partially equipped, but, in contrast with the Republicans, this situation improved enormously for the Free State (see Appendix J). While it was estimated that the Republicans began the war with as little as 6,780 rifles, the Free State had received delivery from Britain of 27,400 rifles, as well as 249 machine guns, by 2 September. (66) The Republicans only source of arms was either those captured from the enemy (or supplied by turncoats) or through the arranging of covert shipments from abroad, an option that was not helped by the Republicans’ financial difficulties and the coastal patrols conducted by British and Free State naval forces. (67) Although a variety of firearms were used on both sides, the principle infantry weapon became the .303 Lee Enfield rifle. Training was rudimentary, as is indicated by Gen. Mulcahy’s comment that, “Men were taught the mechanism of a rifle very often on the way to a fight.”, a state of affairs that applied to both sides. (68) The Irish Civil War was the first conflict to see the widespread use of the Thompson submachine gun. (69) Heavier squad level support was usually provided by a Lewis machine gun.

The war saw the extensive use of armored cars and armored personnel carriers (see Appendix K). While the Free State obtained their vehicles from Britain, the Republicans were characteristically forced to rely on capturing equipment and even constructed a number of improvised armored cars. The most common vehicle was the Lancia armored personnel carrier (APC); an open top armored truck that had been constructed for the Royal Irish Constabulary during the War for Independence. Some, nicknamed ‘Chicken Coops’, had been fitted with wire screens to protect the open top from grenades. In order to increase the number of armored cars available to the Free State Army, sixty-four Lancias were provided with armored roofs and armed with a single Lewis gun.

They received the colorful nickname of ‘Hooded Terrors’. The best armored car that was used in the war was the reliable 1920 pattern Rolls Royce, which the Irish troops christened ‘Whippets’. Armed with a water-cooled Vickers heavy machine gun in a revolving turret, it could provide sustained fire with devastating results. The Free State also employed a few heavier dual-turret Peerless armored cars. (70)Again, training was rudimentary; the usual method of aiming was to open the breech and sight the target through the barrel. (71) Regardless of the skill with which it was used, artillery proved to be the deciding factor in virtually every major engagement of the war. (72) Only too late did the Republicans realize its value, though even when they obtained an 18 pdr. after the recapture of Dundalk on 14 August the lack of trained personnel, along with the difficulties of transportation and ammunition led them to disable and abandon the gun. (73) Nevertheless, in October Chief-of-Staff Liam Lynch proposed that artillery be purchased from abroad.

By January Lynch had settled on a fantastic plan for obtaining in Germany sixteen mountain guns and four heavy guns. They would be landed, along with 100 or more English speaking instructors, in Munster (later, because of naval patrols, Lynch suggested delivery should either be by submarine or air!) (74) The only notable result of this scheme occurred in May, when Republican representatives made contact with an obscure politician in Munich named Adolf Hitler. (75) The artillery scheme only serves to illustrate how terribly ignorant the Republican military commanders were of the nature of conventional warfare, a fact that would haunt them throughout the course of the war.

THE MAJOR CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR, June-August, 1922.

When the Free State Army began its attack on the Four Courts building the garrison was commanded by Comdt. Paddy O’Brien, but the building also contained twelve members of the Army Executive, including Chief-of-Staff Joe McKelvey, Director of Engineers Rory O’Connor, and Quarter Master General Liam Mellows. (76) The defenders had prepared the enormous complex as best they could with sandbags, barbed wire, trenches dug behind the gates to prevent Free State armored cars from rushing the courtyard, and mines planted on Inns Quay in front of the building. (77) The garrison consisted of roughly 180 men drawn from the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 1st Dublin Brigade, armed with Lee Enfields, Mauser carbines, at least five Thompsons, two Lewis guns, and the Rolls Royce Whippet ‘The Mutineer’.

The men were divided into six sections of roughly thirty each, with one section including the members of the Army Executive serving as common soldiers under the command of Ernie O’Malley, O/C of the 2nd Southern Division. (78) O’Malley was only too aware that a complex as large as the Four Courts needed a minimum of 250 troops to defend it. Both himself and Comdt. O’Brien had worked out a plan of defense with Comdt. Oscar Traynor, commander of the 1st Dublin Brigade: snipers would take up positions around the Four Courts, with some buildings being occupied, the enemy barracks would be surrounded in a similar fashion, streets would be barricaded and bridges blown or blocked to impede movement, and finally the enemy troops surrounding the Four Courts would be attacked from the rear. (79) Unfortunately, the orders to set these plans in motion were never given. The Army Executive felt that, in order to maintain the moral high ground, they should not be the first ones to open fire, so that the Free State troops were allowed to surround the Four Courts without interference. (80) Gen. Tom Ennis commanded the Free State forces involved in the attack, which consisted of troops from his own 2nd Eastern Division and the Dublin Guard under their Brigadier, Paddy O’Daly. At this time the total number of Free State soldiers stationed in Dublin may have numbered as much as 4,000. (81) They were directed to take up positions in the buildings surrounding the Four Courts complex, including the Four Courts Hotel, Chancery Place, and Bridewell Prison.

Snipers were stationed in Jameson’s Distillery and the bell tower of St. Michan’s church. The troops would be supported by two 18 pdrs. under the command of Gen. Emmet Dalton and Col. Tony Lawlor. (82) Lancia APCs were parked in front of the gates and disabled to prevent ‘The Mutineer’ from making sorties against the gun crews. (83)Gen. Dalton stated, “It was my belief at the time that the use of these guns would have a very demoralising effect upon a garrison unused to artillery fire, but I realized that their employment as a destructive agent on the Four Courts building would be quite insignificant.”(84) Neither of these assumptions would prove true. The artillery, stationed across the Lifey on Winetavern Street, opened fire at 4:15 a.m. on Wednesday morning, 28 June. As they fired at fifteen minute intervals, the Republican garrison responded in kind, forcing Gen. Dalton to bring in Lancia APCs to shield the gun crews. (85) The southern wing of the building sustained damage, but as the day wore on it became increasingly apparent to Gen. Dalton that the guns were not having the required effect.

The garrison kept up their fire, using the armored car’s Vickers against the snipers in Jameson’s and St, Michan’s tower. (86) Two additional 18 pdrs. were handed over for Gen. Dalton’s use, but because all of his guns were only supplied with twenty shells each, he became concerned and appealed to the British C-in-C in Ireland, Gen. Macready, for more ammunition. Gen. Macready later related, “I agreed to send him fifty rounds of shrapnel, which was all we had left, simply to make noise through the night, as he [Gen. Dalton] was afraid that if the guns stopped firing his men would get disheartened and clear off.”

The crisis was solved when high-explosive shells arrived by ship from Carrickfergus. (87) Nevertheless, as the battle for the Four Courts continued on into the next day and Republicans from the 1st Dublin Brigade occupied buildings around the city, the British became alarmed. The Free State Army was offered the use of 60pdr. howitzers, while Churchill offered to provide Collins with British aircraft flown by British pilots, but painted in Free State markings, to bomb the Four Courts. Both offers were turned down, presumably because their use would risk too many civilian casualties. (88) By the Thursday, 29 June the Free State commanders had concluded that a breach needed to be effected so that the building could be taken by storm. (89)

One or more guns were moved to Bridge Street to fire across the Lifey against the western wing of the Four Courts, while other guns on Chancery Street were trained on the Records Office behind the western wing, which the Republicans had converted into a munitions factory. (90) By nightfall both sections had been badly damaged, leaving a sufficient breach in the western wing. Storming parties from across the Lifey, along the Quays, and in the surrounding buildings rushed the Four Courts under the cover of rifle and machine gun fire. Just before the attack, Comdt. O’Brien had decided to withdraw the section from the Records Office, but before any orders could reach them a storming party led by Comdts. McGuinness and O’Connor fought their way into the building and captured all thirty-three of its defenders. The detachments advancing along the Quays were not as lucky. The garrison’s Lewis guns kept up a steady fire, wounding Comdt. Joe Leonard. Comdt.Gen. Dermot MacManus, a veteran of Gallipoli, took his place and joined Gen. Dalton in leading troops into the breach.

In all the Free State storming parties lost three killed and fourteen wounded. (91) Inside the Four Courts a barricade was erected in the center of the building below the dome using furniture and barbed wire. ‘The Mutineer’ drove back and forth, strafing the side of the west wing facing the courtyard. But the garrison’s situation was clearly deteriorating. Comdt. O’Brien had hoped that the men of the 1st Dublin Brigade would have broken the siege by now, but the majority had inexplicably taken up position on the eastern side of O’Connell Street; over four blocks away and on the wrong side of the widest street in Dublin. Various plans for escape where suggested, but the Army Executive vetoed them all. Early Friday morning Comdt. O’Brien was wounded by shrapnel, so that Ernie O’Malley took command of the defenses.

The fighting in the morning was interrupted when a cease fire was declared so that the wounded could be evacuated. (92) Afterward fighting recommenced, with ‘The Mutineer’ continuing to pepper the Free State foothold in the corridors of the west wing. Comdt.Gen. MacManus returned fire with a Lewis gun and managed to damage the tires, so that the crew chose to abandon their vehicle. By now the shelling had ignited serious fires that were burning throughout the complex. (93) Around 11:30 a.m. an enormous explosion erupted from the Records Office when the fire finally reached two truck loads of gelignite in the munitions factory. A towering mushroom cloud rose 200 feet over the Four Courts.

The remains of records from as early as the twelfth century rained down upon the city (as Churchill quipped, “Better a State without an archive, than an archive without a State.”). Miraculously no one was killed, though forty members of the storming party were badly injured. Additional explosions, intentionally set or otherwise, occurred during the day. (94) A messenger managed to reach the garrison with orders from Comdt. Traynor to surrender, as he was unable to reach them and had already suffered too many losses in his attempts. Half the garrison wished to continue fighting, while the other half favored surrender. Because the garrison was divided, O’Malley chose to obey the order. At 3:30 p.m. on Friday, 30 June Ernie O’Malley led the 140 survivors of the garrison out of the burning Four Courts building and surrendered to Brig.Gen. Paddy Daly of the Dublin Guard. (95) Against his own preference for guerrilla tactics, Comdt. Oscar Traynor had decided to hold a number of defensive position within the capital until reinforcements could arrive from the country.

On Thursday the majority of the Brigade took up positions on and around O’Connell Street, particularly in a section of the east side of the street that would be known as ‘The Block’, consisting of the Gresham, Crown, Granville, and Hammam Hotels. Holes were made in the adjoining walls to facilitate the safe movement of troops within ‘The Block’. However, much of the Brigade also occupied buildings randomly scattered throughout the city, north and south of the Lifey. The headquarters of the 3rd Battalion, for instance, was in the Swan Pub on the south side of the Lifey. (96) When the Free State Army launched their attack on the Four Courts, Comdt. Traynor had sent out messengers seeking assistance. Although reinforcements arrived from Bray and Rathfarnham, the only I.R.A. commanders from farther afield that replied were the O/C of Belfast and Comdt.Gen. Seamus Robinson, the commander of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade who was also acting commander of the 2nd Southern Division in Ernie O’Malley’s absence, neither of whom reached Dublin in time. (97)

On Saturday, 1 July the Free State forces that had captured the Four Courts were redeployed to deal with Republican positions throughout Dublin. Isolated posts, particularly those south of the Lifey, were brought under attack. The Republican troops in the Swan Pub, for instance, were driven out by fire from the Rolls Royce Whippet ‘The Fighting Second’ commanded by Paddy Griffin. By Sunday the Free State had taken a total of 400 prisoners.(98) These successes allowed Gen. Tom Ennis to concentrate his efforts against ‘The Block’ and its surrounding posts. He ordered that a cordon be established around the area to isolate the Republican forces.

The Republican position in Morans Hotel on the corner of Talbot and Gardiner Streets was fired on by one of the Whippets, but the garrison of thirty men stood their ground. However, when artillery from Beresford place began shelling the building, they attempted to escape to Hughes / Holyhead Hotel, which they were also forced out of, after which they surrendered. By 3:30 p.m. ‘The Block’ itself was brought under fire. (99) By Monday virtually all of the Republican positions south of the Lifey had been cleared and Free State forces were increasing their pressure on ‘The Block’. (100) The government troops managed to capture the National Bank on the corner of Parnell Street, which gave them a clear field of fire the length of O’Connell Street. By noon most of the side streets that had covered the approaches to ‘The Block’ were in Free State hands. That evening Free State engineers tunneled their way through a number of buildings to reach one of the few Republican positions on the west side of O’Connell Street, the YMCA, where they detonated a bomb under its defenders. (101)

The futility of holding fixed positions against superior firepower was becoming increasingly obvious. Therefore Comdt. Traynor ordered most of what remained of the 1st Dublin Brigade to make their escape as best they could, while a token force would remain behind to keep the Free State forces occupied. Monday night seventy men and thirty women evacuated ‘The Block’, which was to be held by fifteen soldiers under the command of the Republican firebrand, Cathal Brugha. On Tuesday Rolls Royce Whippets were used to provide covering fire for detachments of engineers, who drove up in front of the buildings in ‘The Block’, planted incendiary bombs on the ground floor, and then sped away.

Despite the fires, the skeleton force of Republicans remained defiant. That night a field gun was brought up Henry Street, directly across from ‘The Block’. (102) The shelling lasted throughout Wednesday while most of ‘The Block’ burned furiously. Around 5:00 p.m. the flames overwhelmed the Granville Hotel, the Republicans’ last tenable position. Cathal Brugha ordered his men to surrender, but he stayed behind, only to emerge alone with gun in hand. Although the Free State troops had only intended to wound him, his wound proved fatal. Cathal Brugha was the last casualty in the battle for Dublin which had cost both sides sixty-five killed and twenty-eight wounded. The civilian casualties, however, may have numbered well over 250. (103) In response to Comdt. Traynor’s plea a Republican relief force had gathered in Blessington, fifteen miles south of Dublin, by Saturday, 1 July. (104) However, before a drive on the capital could commence a message arrived from Comdt. Traynor in which he ordered them neither to march on Dublin nor defend Blessington if attacked.

Rather, he intended to, “…revert to the tactics which made us invincible formerly.”, that is, guerrilla warfare. (105) As a result, when the government forces attempted to trap their Republican opponents in Blessington with three converging columns, they found that the town had been abandoned.(106) Free State columns were dispatched southward to secure Co. Wexford, as well as to the north, where Comdt. Frank Aiken, O/C of the 4th Northern Division, had taken a neutral stand. On 16 July a coup was conducted in which Comdt. Aiken and 300 of his men were taken prisoner in their headquarters at Dundalk, Co. Louth. (107) Thus, even before the conclusion of the fighting in Dublin GHQ had initiated operations to secure control of the province of Leinster. However, it was in the western province of Connacht and the southern province of Munster that Republican strength was concentrated. In Munster in particular, the 1st and 2nd Southern Divisions represented the largest and most experienced units of the I.R.A. (108) With the capture of Joe McKelvey at the Four Courts, Liam Lynch, O/C of the 1st Southern Division, resumed the position of Chief-of-Staff of the Republican forces. (109) Lynch, who was most familiar with the south, planned to establish a ‘Munster Republic’ which he believed would frustrate the creation of the Free State. The ‘Munster Republic’ would be defended by the ‘Limerick-Waterford Line’. This consisted of, moving from east to west, the city of Waterford, the towns of Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Fethard, Cashel, Golden, and Tipperary, ending in the city of Limerick where, significantly, Lynch established his headquarters. (110) Both sides in the war appreciated the strategic significance of the city of Limerick.

As early as February a military confrontation over the occupation of the city had nearly resulted in the outbreak of war. Gen. Michael Brennan, commander of the only major pro-Treaty unit west of the Shannon river, the 1st Western Division in Co. Clare, stated succinctly, “Whoever held Limerick held the south and the west.” (111) GHQ feared that, with control of Limerick, the Republicans would be able to consolidate their hold on the south and the west, freeing up forces to drive on Dublin (in fact, Lynch had adopted a purely defensive strategy, but such a possibility in the future was not out of the question).

Conversely, if Free State troops held the city, it would serve to cut-off the Republicans in Connacht and Munster from each other and provide government forces with a base for offensive actions against both areas. (112) Like so many other Southern Irish cities and towns, Limerick contained positions held by both sides. The Republicans controlled the four military barracks, with their headquarters in the New (Sarsfield) Barracks, along with the two bridges that spanned the Shannon river. The government forces, consisting of elements of the 4th Southern Division under Comdt.Gen. Donncada O’Hannigan, held the Customs House, the Jail, the Courthouse, Williams Street R.I.C. Barracks, and Cruises Hotel. G.H.Q. ordered Comdt.Gen. Brennan to deploy elements of his 1st Western Division to reinforce Comdt.Gen. O’Hannigan.

Establishing his headquarters in Cruises Hotel, Comdt.Gen. Brennan took control of the Athlunkard bridge located outside of Limerick and providing a secure means of bringing his troops into the city by manning posts along the route in between. (113) But Comdt.Gen. Brennan was at a distinct disadvantage facing the Republicans in Limerick. While they could muster an estimated 700 to 800 armed men, his entire division possessed only 200 rifles, of which only 150 could be spared for the troops joining Comdt.Gen. O’Hannigan (who’s own division possessed only 160 rifles in all). (114) Comdt.Gen. Brennan, however, devised a ruse worthy of John B. Magruder. Detachments of men from the 1st Western Division arrived by train at Long Pavement, marched over Athlunkard bridge, and into the city. Once indoors, their rifles were collected and loaded onto a truck that drove out to Long Pavement, where they would be destributed to the next detachment that arrived. (115) Liam Lynch fell for the ploy and, believing he was facing an opponent of equal strength, signed an agreements with Comdt.Gen. O’Hannigan on 4 July that suspended hostilities, thus buying time for the Free State commanders. Ironically, when G.H.Q. learned of this agreement, they became suspicious of Comdt.Gens. O’Hannigan and Brennan’s loyalties. (116) This produced a dilemma for the two commanders, as summed up by the author Carlton Younger, “because no guns had arrived he [Comdt.Gen. Brennan] had had to negotiate and because he had negotiated no guns were allowed to reach him.” (117)

Gen. Dermot MacManus was sent by G.H.Q. to investigate the situation in Limerick. Upon his arrival he repudiated the agreement of 4 July, though he soon began to see things from Comdt.Gens. O’Hannigan and Brennan’s point of view. Although he wanted to drive the Republicans out of the city as soon as possible, he recognized the weakness of the Free State position, writing to G.H.Q., “Unless rifles and armoured cars arrive within 24 hours of now, 10 a.m. 6/7/22 we will be in very grave danger of disaster.” (118) Disaster, however, was averted the following day when the commanders of the opposing sides signed another truce. Although he remained suspicious, Gen. MacManus was forced to accept the need for a truce so that additional men and equipment could be brought to Limerick. (119) Consistent with his notion of a ‘Munster Republic’ as a stumbling block to the establishment of a Free State, Lynch hoped to limit the scope of the war with his truce, thus providing the potential to negotiate with the government for the rejection of the Treaty. Other Republican leaders, however, wished to pursue military victory in the war and recognized that any truce would favor the Free State position, both in Limerick and in the country as a whole.

Sean MacSwiney correctly observed, “Time was needed by the enemy. To gain time they gave pledges which they broke when it suited their purpose.” (120) It suited the Free State commanders in Limerick to formally end the truce on Tuesday, 11 July, when 150 troops, along with a consignment of arms, arrived from Dublin. (121) Before the renewal of fighting Lynch transferred his headquarters to Clonmel, remarking in a letter to Ernie O’Malley, “The second agreement reached at Limerick has been broken by the enemy…I believe…we will eventually…have to destroy all our posts and operate as of old in Columns.” (122) The Chief-of-Staff’s lack of resolve did nothing for the morale of the Republican defenders of Limerick. Seamus Fitzgerald of the East Cork Brigade complained, “At no time did I see a plan of attack. We never took proper control of communications. There was a complete absence of organised military efficiency [in Limerick].” (123) When suggestions were made that the routes by which Free State reinforcements were reaching the city should be attacked, they were vetoed on the grounds that it would weaken Republican positions within Limerick itself. (124) But despite confusion and adherence to a passive strategy, the Republican forces in the city maintained a stubborn resistance.

By 5:00 p.m. on 11 July Free State forces had occupied additional positions and, at 7:00 p.m. hostilities commenced when troops on Williams Street opened fire on the Republican held Artillery Barracks. (125) Williams Street served as the Free State’s front line, with the Republicans in control of the majority of the city located south of this position. The government position on Williams Street was centered on the R.I.C. Barracks, with strongpoints north of this position in the Customs House and the Courthouse. Farther north, however, the Republicans occupied Castle Barracks, located next to the thirteenth century King John’s Castle, as well as the Strand Barracks across the Shannon river. (126) Streets were barricaded, and snipers ranged from church belfries and upper floor windows. The fighting largely consisted of small scale sallies made by both sides against their opponent’s strongpoints. (127) Needless to say, it was the civilians who suffered the worst: business was brought to a standstill and food became scarce. On Thursday, 13 July, the Republicans compensated for the loss of an outpost and thirteen of their comrades the previous day by capturing the Free State position in Munster Tavern on Lane Street. A counterattack was led by armored cars that smashed their way through the barricades on Lane Street. Government troops advanced as far as the Artillery Barracks, but where driven off, though Munster Tavern was regained. On Saturday an all out attack was launched on

Republican positions in both the Strand Barracks and King John’s Castle, involving armored cars, grenades, machine gun and mortar fire. However, no progress was made. (128) The thick walls of the military barracks occupied by the Republicans demanded the use of artillery, a conclusion that G.H.Q. eventually reached. On Monday, 17 July, Gen. Eoin O’Duffy left Dublin to assume personal control of operations in Limerick and beyond. He brought along a convoy under Comdt. Denis Galvin that included a Whippet armored car, two Lancia APCs, four trucks carrying troops, 400 rifles, ten Lewis guns, 400 grenades, and, most important of all, an 18 pdr. field gun. Gen. O’Duffy established his headquarters north of the city in Killaloe. (129) Alerted to the imminent arrival of substantial Free State reinforcements, the Republicans launched an all-out attack on Tuesday in an effort to drive the enemy out of Limerick. Despite suffering substantial casualties, the government troops held their ground. The following day, Wednesday, 19 July, O’Duffy’s 18 pdr. was positioned on Arthur’s Quay, directly across the Shannon from Strand Barracks. The garrison refused the offer to surrender and the firing began. It took nineteen shells to breach the four foot thick walls, but the garrison remained defiant. The gun was moved across the Shannon where, after firing fourteen more shells, a breach in the rear of the building was made by 8 p.m. Meanwhile, the Republicans in the city had launched a major attack to rescue the Strand Barracks.

Their advance up O’Connell Street, however, was caught in a cross fire of machine gun bullets coming from Free State positions at the ends of Thomas and Williams Streets and from across the Shannon. Back at the Strand Barracks Gen. O’Duffy ordered forward a storming party of twelve soldiers led by Col. David Reynolds and Capt. Con O’Halloran. Hurling grenades before them, they were met by intense fire as they entered the breach. Col. Reynolds was severely wounded, while Capt. O’Halloran was struck by Thompson submachine gun fire in the chest. Nevertheless, government troops pressed forward. While some Republicans were captured, the majority made their escape through the neighboring hospital. (130)

Elsewhere in the city government troops struggled to take control of Republican positions, as fighting lasted throughout the night and continued on into the next day. Opponents exchanged fire across Williams Street from the buildings on either side. A particularly fierce battle developed for O’Mara’s Bacon Factory on Roches Street which could have easily been resolved, had not the 18 pdr. been committed to an attack on the Castle Barracks. The Castle Barracks were soon ablaze, though whether this was due to the shelling or the retreating garrison is not clear. By Thursday, 20 July, it was obvious to the Republican forces that their positions in Limerick could no longer be held. At midnight they set the Artillery and New Barracks on fire and began their withdrawal, leaving by Ballinacurra Road for Mallow and Fermoy (to where Lynch had moved his headquarters once again on 15 July). The battle for Limerick had produced surprisingly light casualties: eight Free State soldiers killed and some twenty wounded, while an estimated twenty to thirty Republicans were killed. (131) Heavier casualties, however, would be sustained during the Free State advance south of the city. While the Free State forces were engaged in clearing the western end of the ‘Limerick- Waterford Line’, progress was also being made on the eastern end. Shortly after becoming C-in-C on 13 July, Michael Collins outlined a plan for an attack on the city of Waterford by the forces in Kilkenny under Maj.Gen. John T. Prout. (132) Waterford looked to be a difficult objective to capture.

The garrison under Col.Comdt. Pax Whelan included the Waterford Brigade and possibly elements from Kerry and from the 1st Cork Brigade (specifically the Student’s Company from University College Cork); a total of between 200 and 300 men (though not all of them were armed). They occupied various positions, the most important of which were the Infantry Barracks (their headquarters), the Artillery Barracks, Ballybricken Prison, and a number of hotels along the Quays as well as the Post Office. These latter positions covered the Suir river, some 250 yards wide. The cantilever bridge spanning the river was kept raised. However, because the Republicans had chosen the waterfront as the city’s principle line of defense, they failed to place any troops on Mount Misery, which provided a commanding view of the Waterford from the left bank. (133) Collins ordered troops from the Thurles-Templemore area and the Curragh to reinforce Maj.Gen. Prout (although the latter never reached him), bringing his forces up to a total of between 600 and 700 men. (134) Drawing on the information gathered in a personal reconnaissance by Col. Tom Ryan, Maj.Gen. Prout’s 2nd in command, Col. Patrick Paul, produced three alternate plans: to cross up river to attack the Republican left flank, to cross down river and attack their right flank, or to assemble a column composed of three or four Whippet armored cars in the lead, followed by a number of trucks carrying infantry, that would rush the bridge, securing it before it could be raised.

Once it was learned that the bridge had already been raised, the third plan was ruled out (the required number of armored cars were not available in any case). It was also feared that a river crossing west of Waterford would be vulnerable to an attack by Republican forces from the south or further west. Therefore, Maj.Gen. Prout settled on the first option. (135) On Tuesday, 18 July, Maj.Gen. Prout’s forces left Kilkenny and, after some delays due to road blocks, reached Mount Misery in the late afternoon. He divided his troops into three detachments and established his headquarters in Fleming’s Castle. At 6:45 p.m. scouting parties on the hill were fired on by Republican positions along the Quays, so the troops took cover on the reverse slope, where they would remain that night. (136)

Col. Paul, who directed the operation in person, hoped to keep casualties on both sides to a minimum, a decision that was probably influenced by the fact that he was a native of the city of Waterford. To this end he planned to use the forces’ solitary 18 pdr. to intimidate the Republicans, “Our objective was to break their morale. They had no experience of shell fire and the effects of high-explosives on men who had never known them can be imagined.” (137) Col. Paul was speaking from experience, for like his superior, Maj.Gen. Prout, he was a veteran of the Great War. (138) At 10:40 a.m. on Wednesday the modest barrage commenced. Col. Paul’s initial attempts to shell the city with indirect fire from the reverse slope proved useless, so he brought the gun up to the crest of the hill, where it drew fire from the Quays. Huddled behind the gun shield, Col. Paul directed the gunner to shell the Infantry Barracks, Ballybricken Prison, and the Artillery Barracks. Using the twin towers of the prison as a guide, a few shrapnel shells were fired to adjust their aim before they began raining high-explosive shells down upon the Republican strongholds. To Col. Paul’s embarrassment, one shot fell short of the Infantry Barracks and hit his own home. Nevertheless, enough shells reached the target to convince the enemy that they were under attack from a battery of four guns.

But the defiance of the Republicans, particularly those stationed in the Post Office, showed no sign of weakening. Their fire actually increased with the conclusion of the bombardment, so that Free State troops were prevented from approaching the banks of the Suir to attempt a crossing. Therefore, shelling began again at 5:00 p.m. and lasted for four hours. (139) That same night a detachment of 100 troops under Capt. Ned O’Brien left Giles Quay in a number of row boats and reached the opposite bank a mile east of the city. Making their way silently in the dark, Cpt. O’Brien took the Republican positions along the Quays by surprise at 1:45 a.m. on Thursday, 20 July. He managed to capture twelve prisoners and established a bridgehead in the former

Republican positions in the Country Club, and the Adelphi and Imperial Hotels.(140) For their part, the Republicans had pinned their hopes on a plan to launch a surprise attack on Maj.Gen. Prout’s troops. Comdt.Gen. Denis Lacy had assembled a force to the west of the city in Carrick-on-Suir that consisted of three columns of fifty men each: one from Cork under Jim Hurley, one from South Tipperary under Michael Sheehan, and one from Kilkenny under Andrew Kennedy. They made their way to Mullinahone, where they were joined by 100 men under Comdt. Dan Breen. They pressed forward towards Mullinavant, from where it was intended that Jim Hurley’s column would attack the Free State troops on Mount Misery from behind, while the other two columns would take up defensive positions to guard against government relief forces coming from Kilkenny. Comdt. Breen’s force would remain in reserve.

Unfortunately for the Republicans, Michael Sheehan’s column made an unauthorized attack on a Free State supply convoy in Mullinavant. Comdt.Gen. Lacy assumed that the element of surprise had now been lost and led the entire force back to Carrick-on-Suir, blocking roads and destroying bridges as he went. In fact, Maj.Gen. Prout disregarded this skirmish at Mullinavant and remained completely unaware of the Republican’s intended counterattack. (141) Despite achieving a bridgehead on the city’s Quays, the Post Office remained in Republican hands, and machine gun fire from there prevented the Free State troops on the right bank from reaching the mechanism for the bridge and lowering it.

Maj.Gen. Prout ordered the 18 pdr. to be moved down from the crest of Mount Misery to Ferrybank, from where it fired six shells at the Post Office between 4:00 and 5:00 p.m. But it was the actions of two intrepid soldiers who silenced this position when they took the six or seven Republicans in the Post Office by surprise. (142) Col.Comdt. Whelan could see that his position was now hopeless and ordered the barracks to be set on fire and the majority of his garrison to abandon the city. When it was learned that government troops had crossed the Suir, a column under Comdt. Murray had been dispatched to Col.Comdt. Whelan’s aid, but, having been delayed at Dungarvan for three hours, it only arrived after the Republican retreat had begun and was turned away. (143) Col.Comdt. Whelan left a rear guard in the city under the command of Capt. Jerry Cronin, so that fighting within the city continued into Friday afternoon. Although Capt. Cronin and eighteen of his men were captured with the fall of his headquarters, the Granville Hotel, pockets of Republican troops, particularly the fifteen men in Ballybricken Prison, stubbornly held out.

The 18 pdr., shielded by a Lancia APC, was trained on the building. It took five shells to breach the walls, after which the defenders surrendered. (144) In all ten men were killed in the battle for Waterford. Maj.Gen. Prout returned to Kilkenny, leaving Col. Paul in charge of the city, where a consignment of 500 rifles arrived on the gunboat ‘Helga’ to equip the expected recruits for the Free State forces. (145) To the frustration of the G.H.Q., Maj.Gen. Prout failed to take advantage of his victory by conducting a close pursuit of the retreating Republicans. Nevertheless, on Monday, 24 July, he began his advance on Liam Lynch’s former headquarters, the town of Clonmel. Maj.Gen. Prout’s operation was to coincide with an offensive from Kilkenny in the north by a force under Comdt. Liam McCarthy. Although stiff resistance was encountered along the way, Carrick-on-Suir fell to Free State forces on Thursday, 3 August, and Clonmel was captured a week later. (146)

The relative ease with which government forces rolled up the ‘Limerick-Waterford Line’ from the east, however, was not mirrored in Gen. O’Duffy’s advance southwards from the city of Limerick. The Republican forces under Comdt.Gen. Liam Deasy that had withdrawn from Limerick concentrated in the town of Kilmallock, the northern approach to which was guarded by the towns of Bruree to the west and Bruff to the east. Here more than anywhere else during the Irish Civil War the opposing sides would hold something like clearly defined front lines; each side maintaining a string of outposts in villages and towns, at crossroads, and upon hillocks, with a ‘No-Man’s Land’ varying in width between a few 100 yards to a mile. (147) Within the Kilmallock -Bruff-Bruree triangle would occur the war’s most intense two weeks of fighting. The reason for this was that the Free State troops, the majority of whom were raw recruits, were facing the best of the Republicans forces without any clear advantage in numbers or equipment. (148) Gen. O’Duffy estimated that while his forces had some 1,300 rifles, the Republicans could muster over 2,000, stating, “We are operating in large areas with nothing better than a Rifle. I estimate that the Irregulars [Republicans] have 4 Lewis Guns…for our one… As regards Rifles, the last rifle is distributed and I have none for recruits coming in.”(149) The General complained about the quality of his personnel (though doubtlessly with some exaggeration): ”We had to get work out of a disgruntled, undisciplined and cowardly crowd.

Arms were handed over wholesale to the enemy, sentries were drunk at their Posts, and when a whole garrison was put into the clink owing to insubordination, etc. the garrison sent to replace them often turned out to be worse, and the Divisional, Brigade, Battalion and Company officers were in many cases, no better than the Privates.” (150) The poor quality of their opponents was not lost on the Republicans. Adjutant Con Moloney noted, “He [Gen. Deasy] is confident of success, as any time his forces have met in this area, the enemy ran away.” (151) Nevertheless, the Republican commanders had their own problems. Their logistical support was unreliable and cooperation between units from different Counties was often poor. (152) Gen. O’Duffy drew up the plans for the advance on Kilmallock with the assistance of his 2nd-in-Command, Maj.Gen. W.R.E. Murphy. Maj.Gen. Murphy had served as an Acting Brigadier General in the British Army during the Great War and was now put in charge of executing operations against Kilmallock. Unfortunately for the Free State troops, his experiences in the trenches appears to have adversely shaped his approach to war. (153) On Sunday, 23 July, government forces, already in possession of the town of Bruff, began their advance on Kilmallock.

The movement of troops, in Lancia APCs and on foot, was hindered by blown bridges, roadblocks, and heavy rain, which did not improve the unpaved roads.(154) Late in the day, at Ballycullane Cross, a Free State column was successfully attacked by elements of the 5th Cork Brigade, supported by an improvised armored car. (155) Early Monday morning a detachment of forty-seven men under Comdt. Cronin at Thomastown fought a five hour battle against Republican forces supported by an armored car that ended with their surrender. At the same time Republican forces managed to recapture the town of Bruff. In two days the Republicans had managed to capture seventy-six soldiers, along with their arms and ammunition. O’Duffy was forced to call a halt to any further advances until reinforcements could be brought up. (156) Although they managed to take back the town of Bruff, Free State forces received the worst of it through the rest of the week. On Tuesday, 25 July, a unit of the Dublin Guards under Comdt. Tom Flood was ambushed in a narrow sunken road flanked by hedges. It was some time before the detachment had fought its way clear, having had three men killed and one fatally wounded. (157) Nevertheless, Maj.Gen. Murphy managed to launch a determined attack on the town of Bruree by Sunday, 30 July. Diversionary fighting was conducted all along the front to contain Republican forces in the vicinity of Bruree, while the newly recovered town of Bruff was used as the jumping off point.

The main assault, directed by Maj.Gen. Murphy himself, began at 6:00 p.m., with the troops supported by a number of Whippet armored cars and an 18 pdr. field gun. While the attention of the defenders was fixed upon these forces, Comdt. Tom Flood attempted to take the town by surprise from the southeast with a detachment of Dublin Guards. The Republican defenders, however, were not fooled and stubbornly held their positions for five hours, so that artillery was needed to decide the issue. (158) Comdt.Gen. Deasy knew that Bruree was vital to the defense of Kilmallock. As such, a novel plan was hit upon for its recapture. It would involve the use of three improvised armored cars carrying assault troops armed with rifle grenades, a trench mortar, and a total of ten machine guns. Each vehicle was detailed to eliminate one of the three posts held by enemy forces in Bruree. At 2 a.m. on Wednesday, 2 August, the Republicans captured the town of Patrickswell, only ten miles south of the city of Limerick. From here the armored cars set out for Bruree, where their arrival took the sentries completely by surprise. The lead armored car attacked Comdt. Flood’s headquarters in the Railway Hotel. The Commandant and his men managed to escape out the back of the building under the cover of Lewis gun fire from a water tower. The second armored car rammed the front door of the school house, which persuaded the twenty-five troops inside to surrender. The third armored car, however, had developed engine trouble and was far behind. Word of the attack was transmitted to Comdt.Gen. Seamus Hogan, who personally led the relief forces riding in the Whippet armored car ‘The Customs House’. Having failed to secure the surrender of the town and with reinforcements approaching, the Republican troops decided to withdraw. As their armored cars sped down the road to Kilmallock, ‘The Customs House’ arrived in Bruree. To everyone’s surprise, however, the large vehicle that was followed ‘The Customs House’ turned out to be the third Republican armored car, ‘The River Lee’. Seeing that the town was still in Free State hands, ‘The River Lee’ also fled down the road to Kilmallock, with Comdt.Gen. Hogan in pursuit.

When he rounded a bend in the road, Maj.Gen. Hogan came upon, not only ‘The River Lee’, but the other two Republican armored cars as well. Perhaps then it was lucky for him that the Vickers machine gun in ‘The Custom House’ jammed and he was forced to break off the engagement. (159) The failure of the Republican armored assault on Bruree was followed by Free State preparations for the capture of Kilmallock, which was expected to involve heavy fighting. Adjutant Con Maoloney commented on 2 August, “Up to yesterday we have had the best of the operations there [the Kilmallock area]. There will, I fear, be a big change there now as the enemy have been reinforced very considerably.” (160) On Thursday, 3 August, government forces, consisting of some 2,000 troops supported by armored cars and artillery, began a steady advance on a wide front towards Kilmallock: from Bruree in the west, Dromin in the north, and Bulgaden and Riversfield House in the east. (161) More reinforcements arrived the next day in the form of 700 troops, an additional armored car and another 18 pdr. field gun, all of which were committed to the offensive. By Saturday, 5 August, Free State forces surrounded the town: the main force with artillery faced it from the north, while Comdt. Flood’s troops from Bruree and the forces from Riversfield House were in position to prevent the Republican defenders from escaping to Charleville in the west or Buttevant in the south. Three-and-a-half miles from Kilmallock the artillery was deployed, from where it shelled Kilmallock hill, a dominant position half a mile north of the town. At 10:00 a.m. fire was also directed at Republican troops on Quarry Hill, who were delaying the advance. After some fighting on the fringes of Kilmallock, the two hills were occupied by Free State troops. Pausing to consolidate their positions, Free State forces entered the town, only to find a small rearguard composed of volunteers from Cork. Comdt.Gen. Liam Deasy’s forces had long since departed for Charleville. (162) It was not the overwhelming strength of the Free State forces opposing them in the Kilmallock area that had led to their withdrawal, but rather it was the arrival of government troops deep in their rear, within the ‘Munster Republic’, that forced Comdt.Gen. Deasy to abandon his defensive struggle. (163) Free State expeditionary forces had landed by sea on the coasts of Cos. Kerry and Cork, on 2 and 8 August respectively (see Appendix M). The landing in Co. Kerry had forced Comdt.Gen. Deasy to release units from this area to return home. Although the landing in Co. Cork occurred after the Republicans had withdrawn from Kilmallock, the loss of the Brigades from Cork as well only compounded Comdt.Gen. Deasy’s problems.

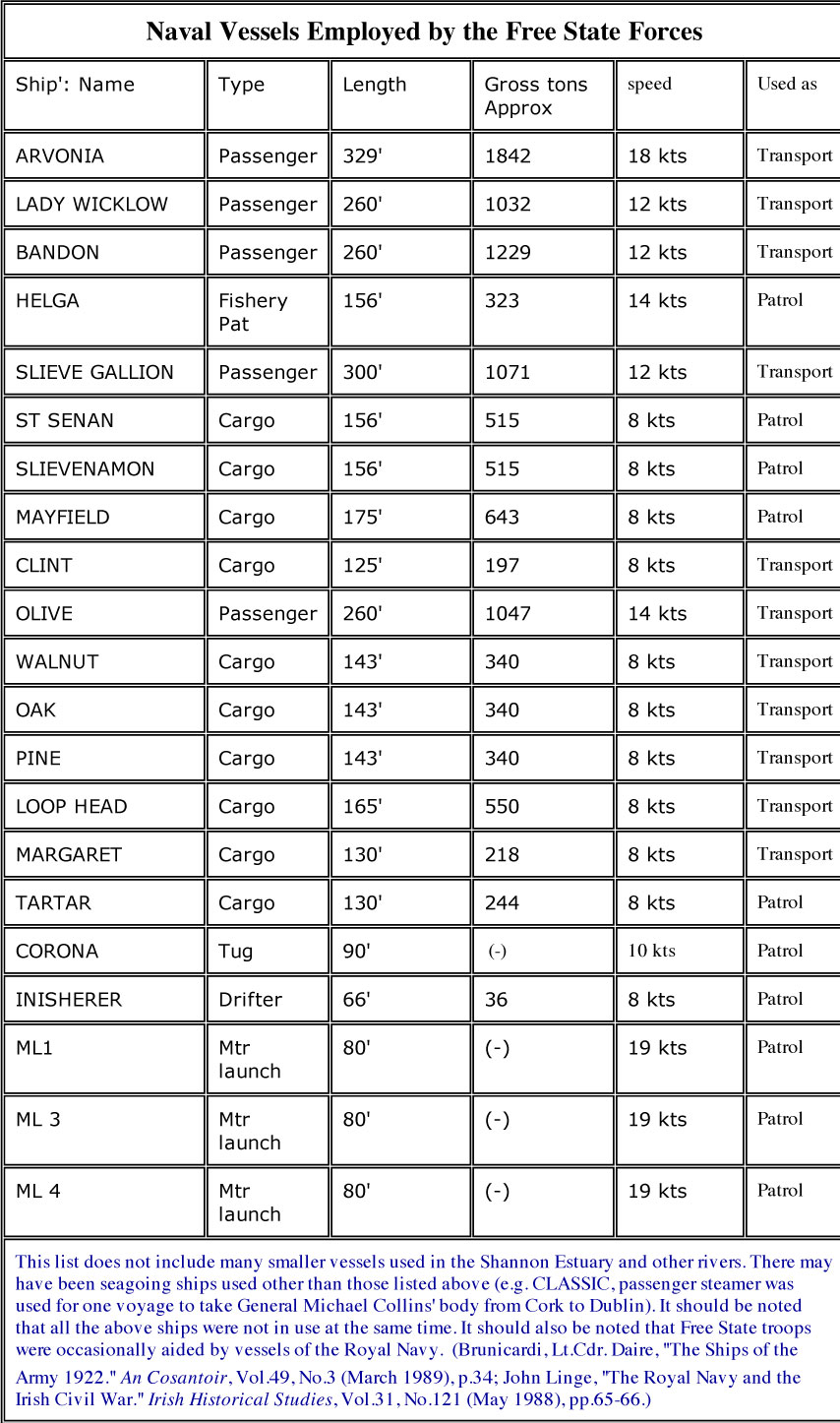

The first naval landing attempted by the Free State Army, which may have been intended as a trial run of this type of operation, had occurred on the coast of Co. Mayo in the western province of Connacht. Brig.Gen. Joseph Ring and Col.Comdt. Christopher O’Malley were assigned command of a detachment of 400 troops, supported by a Whippet armored car and an 18 pdr., that boarded the cross-channel ferry ‘Minerva’ in Dublin. The ‘Minerva’ sailed around the north of Ireland and down the western coast to Clew Bay, where it arrived in the early morning of Monday, 24 July. Rather than put up any resistance, the Republicans set the barracks on fire and fled. From Westport, the Free State forces drove inland to linkup with a column from Gen. Sean MacEoin’s command at the capital of Mayo, Castlebar. (164) Sea-borne landings had been the brainchild of Maj.Gen. Emmet Dalton, who pointed out the disadvantages of advancing overland into the heart of the ‘Munster Republic’, where rail lines and bridges would be destroyed and Free State columns would have to make their way through countryside that favored guerrilla tactics. (165) The strategy of relying on naval landings was not without its critics. Deputy Chief-of-Staff Comdt.Gen. Eoin O’Duffy stated in a letter to Chief-of-Staff Gen. Richard Mulcahy on 26 July, “I would consider a landing …anywhere on the Cork or Kerry coast, unwise for the present. There would be an immediate concentration of Irregulars [Republicans] and our troops would be immediately surrounded. They might make a fight, but I fear that would be all.” (166) C-in-C Michael Collins, however, adopted the idea with enthusiasm, all the more so in light of the difficulties government forces were having in the Kilmallock area. To aid in the advance in this theater, an expeditionary force was organized in Dublin. On the evening of 31 July 450 Dublin Guard, commanded by their founding officer, Brig.Gen. Paddy O’Daly, boarded the cross-channel steamer ‘Lady Wicklow’ at South Wall. A Whippet armored car and an 18 pdr. field gun were also brought on board. At 10:30 a.m. on 2 August ‘Lady Wicklow’ approached the village of Fenit, where there was a pier that extended 600 yards from the shore. The troops remained below deck until the ship was alongside the dock, when they rushed up topside and ran along the pier to the shore. Although the garrison of twenty Republicans opened fire on the invaders, machine guns on the ship, including the Vickers of the armored car, suppressed the defenders’ fire. Fenit was captured in no time and the force advanced the short distance to Tralee, where they defeated elements of the 1st Kerry Brigade and secured the city by 6:30 p.m. (167) The operation was far from bloodless, however, as nine government soldiers had been killed and thirty-five wounded.

(168) The following day, in support of Brig.Gen. O’Daly’s advance out of Tralee, a force of 240 troops drawn from the 1st Western Division under the command of Col.Comdt. Michael Hogan crossed the Shannon estuary from Kilrush to Tarbet in three small fishing vessels, from where he advanced to Ballylongford and Listowel. (169) The most elaborate and decisive naval landing was that conducted against the city of Cork, considered the capital of the ‘Munster Republic’ and certainly the last major city remaining under Republican control. The plan was the joint creation of C-in-C Michael Collins, Chief-of-Staff Gen. Richard Mulcahy, and Maj.Gen. Emmet Dalton, who would personally command the operation. Information on Republican forces were provided by intelligence contacts and a reconnaissance flight flown by Col. C.F. Russell of the fledgling Irish Air Corps (see Appendix L). (170) On Monday, 7 August, the two cross-channel steamers ‘Arvonia’ and ‘Lady Wicklow’ (the latter having returned from the landing in Co. Kerry) were commandeered by the Irish Government. Not surprisingly, the predominantly Welsh crew of the ‘Arvonia’ were less than enthusiastic about her new role as troop transport. Maj.Gen. Dalton’s expeditionary force consisted of roughly 800 men supported by two Peerless and one Whippet armored car, and two 18 pdrs, along with several Lancia APCs. Some 200 of these troops were raw recruits who would receive rudimentary firearms training during the voyage. Maj.Gen. Dalton accompanied the 456 officers and men on the ‘Arvonia’. Additional troops and equipment were loaded onto other ships for landings in support of the Cork operation. (171) The transports left North Wall and reached Roche’s Point at 10:00 p.m. on 7 August. A pilot from Cork harbor was brought aboard the ‘Arvonia’, unaware of her mission. When he seemed reluctant to provide the necessary aid in navigating the harbor, Maj.Gen. Dalton did not hesitate to draw his side arm to help persuade him to cooperate. Initially Maj.Gen. Dalton had hoped that they could dock at Ford’s Wharf, near the city, but the pilot informed him that a ‘blockship’ had been sunk to bar the way. The only other deep water berth that was not mined was Passage West. Steering their vessels around another ‘blockship’, the ‘Owenacurra’, the Free State flotilla reached Passage West early Tuesday morning, 8 August. (172) At 2:00 a.m. Maj.Gen. Dalton ordered Capt. Frank O’Friel to take twenty men from his Company by boat to the shore and reconnoiter the area. Upon his return, Capt. O’Friel reported that the Republican guards had abandoned their post with the appearance of the ‘Arvonia’ and ‘Lady Wicklow’ (having captured a few of them), so that it was safe to land. Maj.Gen. Dalton waited until dawn to disembark three Companies of fifty men each, supported by an armored car and an 18 pdr., in order to form a protective screen a half a mile around Passage West.