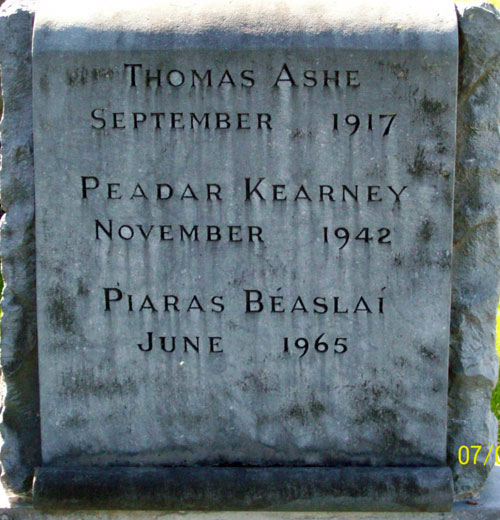

Piaras Beaslai, Peader Kearney, Thomas Ashe

(Buried; Glasnevin Cemetery)

Piaras Béaslaí was born and educated in Liverpool where he became a journalist and editor of the Catholic Times. In 1904 he moved to Dublin and joined the Gaelic League and in 1911 he founded The Society of Gaelic Writers and the newspaper An Fáinne to promote the Irish language. In 1914 Béaslaí joined the Irish Volunteers and in 1915 he published his first play Fear na Milliún Púnt. It was Béaslaí’s speech to the National Congress of the Gaelic League in 1915 which inspired Padraig Pearse’s oration at the graveside of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in the same year.

During the 1916 Easter Rising Béaslaí was Vice-Commandant of the 1st Dublin Battalion of the IRA which occupied North King Street. After the Rising Béaslaí was sentenced to ten years penal servitude but he escaped, was recaptured and imprisoned in Strangeways Prison, Manchester. Béaslaí also escaped from that prison and went back to Ireland where he became IRA Director of Publicity. In the General Election of 1918 Béaslaí was elected to the First Dáil as Sinn Féin Deputy for East Kerry. In 1920 he published a volume of short stories Bealtaine 1916 agus Dánta Eile. Béaslaí supported the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and toured America giving lectures in support of the Treaty in 1922.

During the Civil War Béaslaí was a Major-General in the Free State Army and Head of Press Censorship. He resigned from the Dáil and the Free State Army in 1923 and 1924 respectively. Béaslaí published several more novels and plays, including Astronár (1928); An Danar (1929) and a collection of Irish poetry and plays, dating from 1600-1850, entitled Éigse nua-Ghaedhilge (1934).

Peader Kearney was born at 68 Lower Dorset Street, Dublin in 1883. His father was from Louth and his mother was originally from Meath. He was educated at the Model School, Schoolhouse Lane and St Joseph’s Christian Brothers School in Fairview, Dublin. He left school at the age of 14, becoming an apprentice house painter.[1]

Kearney joined the Gaelic League in 1901, and joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1903. He taught night classes in Irish and numbered Sean O’Casey among his pupils. He found work with the National Theatre Society and in 1904 was one of the first to inspect the derelict building that became the Abbey Theatre, which opened its doors on 27 December of that year. He assisted with props and performed occasional walk-on parts at the Abbey until 1916.

Kearney was a co-founder of the Irish Volunteers in 1913. He took part in the Howth and Kilcoole gun runnings in 1914. In the Easter Rising of 1916 Kearney fought at Jacob’s biscuit factory under Thomas MacDonagh, abandoning an Abbey Theatre tour in England in order to take part in the Rising. He escaped before the garrison was taken into custody.

He was active in the War of Independence. On 25 November 1920 he was captured at his home in Summerhill, Dublin and was interned first in Collinstown Camp in Dublin and later in Ballykinler Camp in County Down.

A personal friend of Michael Collins, Kearney at first took the Free State side in the Civil War but lost faith in the Free State after Collins’s death. He took no further part in politics, returning to his original trade of house painting. Kearney died in relative poverty in Inchicore in 1942. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. He was survived by his wife Eva and two sons, Pearse and Con.

Kearney’s songs were highly popular with the Volunteers (which later became the IRA) in the 1913-22 period. Most popular was “The Soldier’s Song”. Kearney penned the original English lyrics in 1907 and his friend and musical collaborator Patrick Heeney composed the music. The lyrics were published in 1912 and the music in 1916.[2] In 1926, four years after the formation of the Free State, the Irish translation, “Amhrán na bhFiann”, was adopted as the national anthem, replacing God Save Ireland. Kearney was not paid royalties for his contribution to the song.

Other well-known songs by Kearney include “Down by the Glenside (The Bold Fenian Men)”, “The Tri-coloured Ribbon”, “Down by the Liffey Side” and “Erin Go Bragh” (Erin Go Bragh was the text on the Irish national flag before the adoption of the tricolour).

Kearney’s sister Kathleen was the mother of Irish writers Brendan Behan and Dominic Behan, both of whom were also republicans and songwriters. Brendan Behan was in prison when Kearney died, and was refused permission to attend his funeral. In a letter to Kearney’s son, Pearse, he said, “my Uncle Peadar was the one, outside my own parents, who excited the admiration and love that is friendship.”[4]

In 1957 his nephew Seamus de Burca (or Jimmy Bourke son of Kearney’s sister, Margaret) published a biography of Kearney, The Soldier’s Song: The Story of Peadar Ó Cearnaigh.[3] In 1976 De Burca also published Kearney’s letters to his wife written during his internment in 1921 were published as My Dear Eva … Letters from Ballykinlar Internment Camp, 1921.[3] A wall plaque on the west side of Dorset Street commemorates his birth there.

Thomas Patrick Ashe 12 January 1885 – 25 September 1917 was a member of the Gaelic League, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers.

He was born in Lispole, County Kerry, Ireland. Having entered De La Salle Training College, Waterford in 1905 he began his teaching career as principal of Corduff National School, Lusk, County Dublin in 1908. He spent the last years before his death teaching children in Lusk, where he founded the award-winning Lusk Black Raven Pipe Band as well as Round Towers Lusk GAA club in 1906. During the summer of 1913, Douglas Hyde, president of the Gaelic League, attempted to expel him and other members.

Commanding the Fingal battalion of the Irish Volunteers, Ashe took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. Ashe’s force of 60-70 men engaged British forces around north County Dublin during the rising. The battalion won a major victory in Ashbourne, County Meath where they engaged a much larger force capturing a significant quantity of arms and up to 20 Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) vehicles. 24 hours after the rising collapsed, Ashe’s battalion surrendered on the orders of Patrick Pearse. On 8 May 1916, Ashe and Éamon de Valera were court-martialled and both were sentenced to death. The sentences were commuted to penal servitude for life. Ashe was imprisoned in Lewes Prison in England.

With the entry of the U.S. into World War I in April 1917, the British government was put under more pressure to solve the ‘Irish problem’. De Valera, Ashe and Thomas Hunter led a prisoner hunger strike on 28 May 1917 to add to this pressure. With accounts of prison mistreatment appearing in the Irish press and mounting protests in Ireland, Ashe and the remaining prisoners were freed on 18 June 1917 by Lloyd George as part of a general amnesty.

Upon release, Ashe returned to Ireland and began a series of speaking engagements. In August 1917, Ashe was arrested and charged with sedition for a speech that he made in Ballinalee, County Longford where Michael Collins had also been speaking. He was detained at the Curragh but was then transferred to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. He was convicted and sentenced to two years hard labour. Ashe and other prisoners, including Austin Stack, demanded prisoner of war status. As this protest evolved Ashe again went on hunger strike on 20 September 1917. On 25 September 1917, he died at the Mater Hospital after being force-fed by prison authorities. At the inquest into his death, the jury condemned the staff at the prison for the “inhuman and dangerous operation performed on the prisoner, and other acts of unfeeling and barbaric conduct”.

Ashe’s death had a significant impact on the country increasing Republican recruitment, his body lay in state at Dublin City Hall, and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

He was also a relative of Catherine Ashe, the paternal grandmother of American actor Gregory Peck, who emigrated to the United States in the 19th century. The Ashe Memorial Hall, housing the Kerry County Museum, in Tralee is named after him.