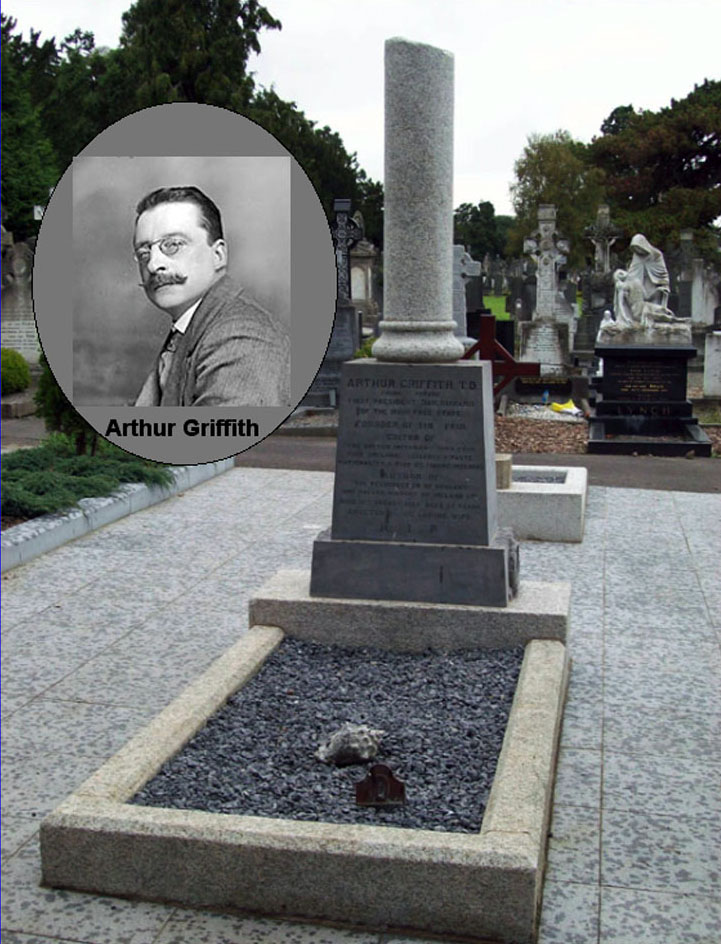

Arthur Griffith

Arthur Griffith (1872-1922), journalist and politician; was born on 31 March 1872 at 61 Upper Dominick Street, Dublin. The son of Arthur Griffiths, a printer, and his wife Mary Phelan. After attending Strand Street and Mary Street, Christian Brothers’ Schools, Griffith followed his father into the printing trade. He worked with the Irish Independent and The Nation. Griffith was strongly influenced by Charles Stewart Parnell, Thomas Davis, and John Mitchel. He was a founding member of the Celtic Literary Society in 1893. His interest in Irish nationalism was reflected in his membership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and the Gaelic League. The recession of 1896 prompted Griffith to travel to South Africa in order to seek employment, where he worked in a diamond mine. He later co-established a small news paper in the Transvaal, where he honed his literary skill. He returned to Ireland in 1898 at the request of his friend Willie Rooney, to edit a new weekly paper, the United Irishman, to which well known Irish writers as George Russell and William Butler Yeats had contributed. Griffith wrote editorials urging the Irish to work for self-government. In 1900, he founded Cumann na nGaedheal, a cultural and education association aimed at the reversal of anglicisation.

Griffith wrote articles condemning the visit of King Edward VII to Dublin in 1903. The fall of Parnell in 1890 extinguished any hope of winning independence by constitutional means. In 1904 Griffith published a pamphlet on the 1848 Hungarian Revolution entitled The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland in which he set out his ideas on Irish independence under a dual monarchy, like that of Austria-Hungary. In 1905 Griffith expounded the policy, which emphasised the idea of national self-reliance. He set up a movement under the name Sinn Féin meaning ‘ourselves’. This movement represented a combination of a number of groups at the time including Cumann na nGaedhael, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council. It acted as an umbrella organisation incorporating all brands of nationalism with the exception of Home Rule. When the United Irishman ceased publication in 1906 as a result of a libel action, and Griffith started a new paper, Sinn Féin.

Griffith was disappointed at the concessions offered to Irish nationalists in the Home Rule Bill of 1912 and as a result he joined the Irish Volunteers to counter Unionist opposition to Home Rule. He was involved in the landing weapons for the volunteers at Howth in July 1914. At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 thousands of young Irishmen responded to Redmond’s call and joined the British army. Griffith urged them against this course of action. Soon after Griffith’s paper Sinn Féin was suppressed.

Griffith was not actively involved in the 1916 Rising. This affected his standing with the dominant, military wing of the Volunteers. However, the British Government realised the effect of his writings in reviving the national spirit, and he was imprisoned along with those who had fought in the Easter Rising. After the execution of the leaders, public opinion, until then either lukewarm or antagonistic, turned in favour of Sinn Féin. A convention in Dublin in October 1917 showed the increased strength of the movement. In the popular mind the term Sinn Féin included all fighters for Irish freedom. Griffith stood down as president of Sinn Féin in favour of de Valera.

In the general election of 1918 Sinn Féin had an overwhelming victory. Grifffith retained the East Cavan seat he had won in the by-election earlier that year. The elected Sinn Féiners, followed Griffith’s policy of absenteeism from Westminster. Instead they assembled as Dáil Eireann in Dublin in 1919, proclaimed themselves the parliament of Ireland, and declared a republic. They had gone farther than Griffith, who had not envisaged a complete constitutional separation from England. De Valera was elected president of the republic and Griffith vice-president. While de Valera was in the United States from June 1919 to the end of 1920 to enlist American support, Griffith acted as Head of the Republic. During this time the War of Independence against British occupation was being waged in Ireland. His policy was now put into practice; town and county councils ignored the British authorities in Dublin, and Sinn Féin courts were set up and functioned with remarkable success. Over large parts of the country British rule ceased to operate. This civil resistance was buttressed and accompanied by guerilla warfare under the leadership of Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy. Griffith was arrested in November 1920 and imprisoned in Mountjoy Jail until July 1921.

The pressure of public opinion in America and Britain led to a Truce in July 1921. Griffith was chosen to lead the Irish delegation in London that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921 that established the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth. Griffith regarded the Anglo-Irish Treaty as the best that could be achieved for Ireland. In the debates that later followed in the Dáil, Griffith defended the Treaty, arguing that it gave Ireland the opportunity to advance to full freedom. Following its ratification, de Valera resigned and Griffith was appointed President of the Dáil. They were to face strong opposition from the anti-Treatyites and the whole episode sparked a bitter, destructive civil war. The troubles continued for several months, by means of guerilla warfare. Griffith was a prolific poet and wrote under various pseudonyms. His Songs, Ballads and Recitations were published posthumously in 1923. Griffith, exhausted by his labours, died of a brain haemorrhage in Dublin on the 12 August 1922 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. He married in 1910 and was survived by his wife, a son and daughter.