The Granard Connection

DIARY

Conor Gearty ( Son of Margot Gearty & Grand-nephew of Kitty Kiernan)

It was only after the IRA ceasefire that I began once again to be proud of my family’s political past. For more than two generations, it’s been doctors, solicitors, dentists and teachers. Like many Irish families we’ve been happy to lengthen our names with the prefixes and acronyms of professional achievement, while glossing over the patriotic killing and the willing sacrifice of an earlier generation that fought two terrible wars for our unborn lives. Now, after Canary Wharf, Manchester and Lisburn, it should have been back to silence and material success. But a complication has emerged, which threatens to bar our family’s return to its amnesiac state. Michael Collins, Neil Jordan’s film, is not about us as a family, but we are part of its revolutionary story and provide much of its romance.

In May 1917, Michael Collins came down for a few days to Longford, one of those anonymous midland counties that tourists in Ireland pass through quickly on the way to somewhere they’ve been told to go. It is a boggy and flat array of fields, interrupted by a few main streets calling themselves towns. Only the partisan eye would call it beautiful, which I do, but then I was born and reared there, going first to school at Granard’s Convent of Mercy and then on to Abbeylara National, where I had three classmates until amalgamation with Springstown swelled our numbers to eight. Back in May 1917, Longford was briefly in the imperial eye. Joe McGuinness, a Sinn Fein prisoner interned by the British after the Easter Rising, had the temerity to challenge the established Irish party for a seat at Westminster. It was to help run McGuinness’s by-election campaign on behalf of their new party that Collins had come down. The place was plastered with pictures of McGuinness in his prison uniform, under the slogan ‘Put him in to get him out.’

Astonishingly, Joe McGuinness won the seat, by 37 votes. He was the first Sinn Feiner elected to Westminster and his success gave an inkling of the great triumph that the Party was to enjoy in the 1918 General Election. It certainly helped McGuinness that his family were well-established in Longford. His niece married a local man and their second son, born in 1930, was my father. As a child, I used to help out at one of the two stores run by Auntie Bee, Joe’s spinster niece. This McGuinness background was a great source of pride to all of us, in those days in the Sixties when it was not complicated to be a Republican. I used to wish that McGuinness was my surname and not this Gearty one that no one could pronounce.

While Collins was campaigning in Longford, a relation of McGuinness’s, Brigid Lyons Thornton, suggested that he stay in the Greville Arms Hotel in Granard, a small town 16 miles from Longford town. ‘Auntie Thornton’, as we called her, was also involved in the Republican movement: on this occasion, however, it wasn’t subversion but match-making that was on her mind. Collins might have been a revolutionary leader in the making, but he was also a grand fellow from west Cork and Auntie Thornton thought he should meet the Kiernan girls from Granard.

The Greville Arms was a small family hotel run by Larry Kiernan and his four sisters, Chrys, Kitty, Helen and Maud, all ‘lovely glamorous girls’, as Auntie Thornton described them to Collins. When their parents died within a couple of months of each other in 1908, Larry, then aged only 17, was left at the helm of a business that included not only the hotel but also a grocery and hardware store, a timber yard and an undertaking business. His sisters were no ordinary country girls. The family’s guardian and relative Andrew Cusack, a draper in the town, arranged for them to be sent as boarders up to Dublin to be educated in Padraig Pearse’s experimental school, St Ita’s. This was an extraordinary decision for any family in Ireland at that time, even more so for one from the depths of the country. St Ita’s was a place where young ladies visited museums in school hours, held classes in the garden and immersed themselves in Ireland’s Celtic culture. The girls there read Yeats and Synge as contemporary writers and steeped themselves in the myths and folklore of ancient Ireland. Above all, they encountered advanced Irish nationalism as a political force. One of their teachers was the daughter of the legendary Charles Gavan Duffy, who led a noble but futile revolution against the British at the height of the Famine in 1848. A few years after the Kiernan girls left his school, Pearse was executed by the British for leading another rebellion.

The Kiernan sisters took a bit of the creative atmosphere of St Ita’s back to Granard on their return. By the time Collins came to stay, they were helping Larry to run the family’s concerns with bohemian zest and flair. They had their clothes designed by a cousin (another Granard adventurer, who had been tutor to a maharajah in India), held grand parties and sang and played music together. Their style and beauty drew the county’s talented and hopeful young to the town, and turned the hotel into a centre of elegance and excitement, a kind of Bloomsbury standing alone in the midlands of Ireland. Before Partition and the triumph of the motor-car, Granard was the sort of place where tradespeople happily stopped for a night on the way to Belfast or Dublin or Galway. It was a humming, prosperous town. Larry became chairman of the district council, bred and showed hunters at the Royal Dublin Show and rode with the Longford Harriers.

The Kiernan Family of Granard c 1880’s to 1950s’

Every family has its own unique history. My own particular connection to Granard began the day my grandfather Peter Kiernan walked to Granard in the early 1870s to seek his fortune. Being a younger son, he left his home in the townland of Aughagreagh which is about five miles west of Granard. His family had worked a small farm there for many generations and continue to do so up to the present day.

Within ten years of learning his trade in the grocery/hardware business in Granard, Peter was ready to fulfil his dream of owning his own place. But meanwhile, and most significantly, he had met the woman who would be his wife, his friend and support for the rest of their lives together. Bridget Dawson, of Cloncovid, and Peter Kiernan were married in the old church of Mullahoran, Co. Cavan on October 4th 1886.

Business flourished in their new premises ‘The Corner House’ Granard. Bridget, the Cavan woman, was shrewd and diplomatic while Peter was popular, respected and had a flair for business. A photograph from the Lawrence Collection (late 1890s) shows a thriving and lively three-story premises in a busy town.

The Kiernan family (from left) Lily, Helen, Bridget, Maud, Catherine, Peter, Rose, Christine, and Larry’s foot in stirup

The Kiernan family (from left) Lily, Helen, Bridget, Maud, Catherine, Peter, Rose, Christine, and Larry’s foot in stirup

Having lost their first baby at birth in December, 1887, Bridget gave birth the following year to twin girls Lily and Rose. After them came Christine, Lawrence Dawson, Catherine (Kitty), Helen and Maud in quick succession. The family remembered nothing but happiness from the years that followed. Twenty years later (1921) Kitty would write to her ‘very dear Micheal’ – I’d love to feel you wanted me always beside you just the way Daddy and Mother used to be (Extract from Dermot Keogh and Gabriel Doherty. Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State. Cork.1998. P.38)

Family folklore has it that after a busy day in the shop, the money counted and the children in bed, Peter would take Bridget into ‘the snug’ for a nightcap together. On the night of the 31st March 1901 he must have felt a happy and fulfilled man as he recorded on his census form that seventeen people resided in his home – his wife and seven children, six shop assistants and two domestic servants. He was also in 1899 elected as a member of Longford County Council.

The Front of the Greville Arms Hotel Granard, Co. Longford

The Front of the Greville Arms Hotel Granard, Co. Longford

Peter and Bridget purchased the Greville Arms Hotel after it’s proprietor William Mullen died in 1903. He also bought the shop next door which later became Kiernan Stores which stocked everything (according to adverts) ‘from a needle to an anchor’. Despite all these advances however, there was great cause for anxiety. In 1907 nineteen year old Rose was sent off to a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland in the desperate hope of a cure for her tuberculosis. It was not to be. She died there in a strange land, while her twin sister Lily, too ill for treatment, died at home in Granard on 27th November 1907. Exactly a year later, their mother Bridget died suddenly – her life cut short at only forty five years. Two months later Peter himself died on January 19th 1909.

Their only son Larry (my father) had to return home from St. Mel’s College, Longford to take over the running of this little empire at only seventeen years old. His older sister Chris stayed at home in Granard to help him while Kitty, Helen and Maud were sent by their guardian – their uncle Andrew Cusack – a draper in Granard (where Durkins reside now), to a new experimental school for girls at Cullenswood House, Ranelagh, Dublin. This school was St.Ita’s ,(a sister school to St. Enda’s school for boys in Rathfarnham) – both of which had as their director Padraig H. Pearse, BA, Barrister-at-Law. Sadly, this school closed down in 1912 and the girls all returned home to Granard. Each took responsibility for one or other aspect of their expanding business. A new era for the family had begun.

The following few years have been well documented. Suffice to say that the family settled down to hard work and a variety of social activities bringing with them the creative skills and broad education they had had both at Loreto and at St. Ita’s. Many suitors came on the scene for the four girls but it is Kitty’s blossoming romance with Michael Collins that concerns us here. This was a high profile love affair with hundreds of letters being exchanged between the two – the first being written by Collins in February or March 1919 – the last from Kitty on 17th August 1922.

For the purpose of this article I have included two letters from Michael Collins which have references specifically to Granard and County Longford. Despite the great affairs of State with which he was involved these letters show that he could still take time to show his interest not only in Kitty but in the minutia of life and business in a small midland town.

In one such letter, written on 8th November, 1921, having just arrived back in London for the Conference on the Treaty, he tells Kitty he has just been to at 8a.m.Mass and lit a candle for her. He continues

How did you get on yesterday?. Granard Market is held on an ill-chosen date.Monday – how could anyone be in a proper mood or manner for buying or selling on Monday morning? Of course this is the real explanation of the late hour of starting – isn’t it? Anyway I hope the day was not very strenuous for you and that you got through all right. Let me know please. ( Leon O’Broin. In Great Haste .The letters of Michael Collins and Kitty Kiernan. Dublin 1983)

Then in reply to a letter from Kitty written on May 22nd 1922 telling him of the death of Joe McGuinness (of Longford) whom she describes as “a very genuine sort of man and I liked him very much and got on well with him” Collins writes:-

He is a great loss to us, but apart from that I feel the personal loss much more keenly.He was the one responsible for the recent peace. (ibid)

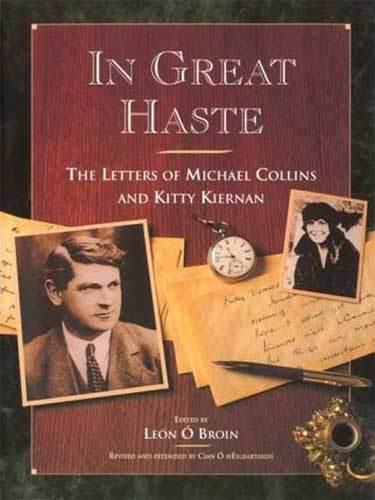

In Great Haste: The letters of Michael Collins and Kitty Kiernan, Leon O’Broin. Dublin, 1983

Towards the end the letters become more somber. Collins and Kitty write to each other of Harry Boland’s death – each stricken by the tragedy and thinking back without bitterness on happier times. Kitty prays all day and goes with Larry to the funeral. Then came Arthur Griffith’s death. Someone has told Kitty, she writes to Collins ‘that if you go to the funeral to-morrow you will be shot, but God is very good to you, and we must do Lough Derg sometime in thanksgiving.

But it was not to be. The awesome tragedy of Collins death at Beal na Blath on August 1922 was the final grief for Kitty, her devastation total. Instead of the planned double wedding – Maud married Gearoid O’Sullivan in October of the same year – Kitty sat by her sister dressed in black from head to foot. My parents Larry and Peggy married in January, 1923 but Kitty does not appear in any of the photos. She lived with them in Granard for a few months, sitting in the drawing-room responding to the thousands of letters she received from Ireland and abroad. When she left to stay with Maud and take up a small government position, she seldom returned. The Pain of the memories was too great. In 1925 she married a friend and colleague of Collins – Major General Felix Cronin and had two sons.

I was born into the Greville Arms in 1933, the youngest of four children of Peggy and Larry. While having a rich and vibrant childhood we were touched by the spirit of the past. As we ate our meals in the coffee room, the framed eyes of Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith looked down upon us from handsome framed portraits on the walls. We children had black-bordered mortuary cards of Michael Collins in our prayer books. When we had measles and mumps the two impressive volumes of ‘Michael Collins’- by Pieras Beaslai were eagerly read.

Old family friends from ‘the Movement’ some by now government ministers or people in high office in the new state – called regularly and spoke of ‘the girls’ in hushed tones. ‘The girls indeed came themselves with their children, bringing excitement and glamour as ever. In 1940 Helen came back to Granard to die –aged only forty, elegant and lovely to the end. Six months later Maud died of the same ailment. Kitty lived only a few more years (1945) and was buried near the grave of Michael Collins at Glasnevin Cemetry. We watched sadly as our parents grieved for ‘the girls’ but on the 22nd December, 1948, a few days before Christmas, my father Larry died suddenly at home and with him the little empire that had been Kiernan’s Stores virtually came to an end. The depression of the 1950s took its toll and the next generation followed other paths. The Hotel changed hands in the early 1960s.

I lived near Granard up to 2004 but still return regularly, sometimes to have lunch in the Hotel or to take my visitors to climb the Moat. I tell them of Collins letter to Kitty written from Cadogan Square Gardens,London SW, on his birthday 16th October 1921, during the treaty negotiations: “and how I wish I were there now – on the Moat. Last time I was on the Moat, early morning,. Do you remember? I looked across the Inny to Derryvaragh over Kinale and Sheelin (and thought of Fergus O’Farrell) and turning westward saw Cairnhill where the beacons were lighted to announce to the men of Longford that the French had landed at Killalla”. (Ibid)

Margot contributed a fuller article called, ‘the Granard Connection’, to an edited volume, Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State, edited by Gabriel Doherty and Dermot Keogh. The collection also includes an article about Gearoaid O’Sullivan, friend of Collins and husband of Maud Kiernan.