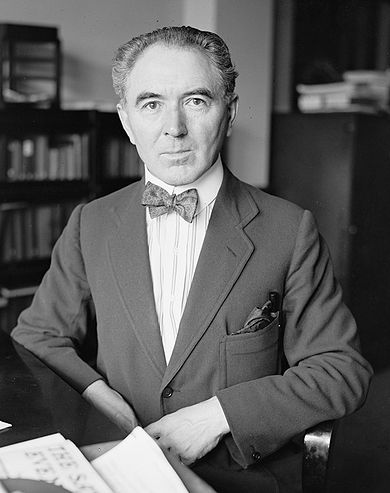

Prof. Timothy A. Smiddy

Professor Timothy A. Smiddy

Timothy Smiddy (1875–1962) was an Irish academic, economist, and diplomat. He is best known as Ireland’s first Ambassador / overseas Minister, serving as Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary to the United States of America for the Irish Free State from 1924 to 1929.

Personal life

Timothy Aloysius “Audo” Smiddy was born on April 30th 1875 in Kilbarry, Co. Cork, the son of William Smiddy, a wealthy merchant originally from Ballymacoda, East Cork, and Honora Mahony, a scion of the Blarney Mahony family. He was educated at St. Finbarr’s College Cork, before attending University College Cork, graduating with a B.A. (1905) and an M.A. (1907). Later he attended universities in Paris, France and Cologne, Germany. At one point, he considered the priesthood. However in 1900, he married Lillian “Muddie” O’Connell, also from Cork city. They had six children including five daughters Pearl (Binnie), Muriel, Cecil, Ita and Ethna, and a son Sarsfield.

Role in Independence

A contemporary and friend of Michael Collins, the Irish revolutionary, Smiddy was appointed by Collins to be his Economic Adviser to Plenipotentiaries for the Treaty Negotiations from October to December 1921 following the War of Independence. This was at a time when Michael Collins was the Minister for Finance in the putative Republic.

Professor of Economics, UCC

Smiddy was first and foremost an academic and an economist. In the College at Cork in the newly constituted National University of Ireland, which replaced the Royal University of Ireland, Smiddy was holder of the Professorship of Economics and Commerce. He served in this post from 1903 to 1924, one of only six to have held the post since the formation of the Department of Mental and Moral Science at the College in 1849. In 1952, he was awarded the Honorary Degree of DEconSc by University College, Cork.

Minister Plenipotentiary

Smiddy was initially appointed as the Irish Free State’s Representative in Washington in 1922. Following representations by the Free State’s government to London and Washington, and in particular to tackle the problem of anti-Treaty propaganda, this role was officially recognised in 1924. From then until 1929, Smiddy served as Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary to the United States of America for the Irish Free State.

Smiddy’s appointment represented not only the establishment of Ireland’s first formal diplomatic relations with another country since independence, but also the first attempt by any British dominion or colony to appoint what would these days be regarded as an Ambassador to a third country. The appointment was also a significant development in the domestic affairs of Ireland, as it was “part of an overall campaign to discredit Republican attacks on the integrity of the Free State and to strengthen the new state’s position by formally demonstrating its essential independence from the United Kingdom.”

Later life

Smiddy also served as the Irish Free State’s High Commissioner to London (1929–30) and was a member of the Tariff Commission (1930–33) and then became chairman of the Commission on Agriculture (1939–1945). Thereafter, he served on various Boards, and was head of Combined Purchasing Section at the Department of Local Government and Public Health from 1933 to 1945. He was also Director of the Irish Central Bank.

Throughout the late 1930’s and the 1940’s, Smiddy advised the de Valera government on economic matters. In particular, he was instrumental in bringing about a universal child allowance. He died in 1962.

The 25th Annual Dinner was held at the Hotel Astor New York,

On the evening of January 20th, 1923.

About two hundred and fifty members and guests were present.

President-General John J. Lenehan presiding.

PROFESSOR TIMOTHY A. SMIDDY’S SPEECH

PROFESSOR TIMOTHY A. SMIDDY’S SPEECH

Professor Timothy A. Smiddy was born in Cork, Ireland, 1879; educated Farra Ferris Seminary, Cork, St. Sulpice at Issy-Sur-Seine, Paris, University College, Cork, graduated National University of Ireland; holds degree of M.A. with honours in philosophy; Professor of Economics, University College of Cork, Senator of National University, 1918-1922; Member of the Labour Board of Ireland; selected by the late General Michael Collins as expert Aid-de-Camp to the Irish plenipotentiaries who went to London for the Conference that resulted in the Irish Treaty; Commissioner of the Irish Free State at Washington, D. C.

President-General Lenehan:

“Professor Timothy A. Smiddy, for years Professor of Economics in the National University of Ireland, has studied at various centers of learning throughout Europe. He is the High Commissioner of the Irish Free State to Washington and the first official representative sent by the Irish Free State, or by Ireland, to this country. He is able, as no other man, to tell us at first hand of political and economic conditions in Ireland and of the prospects of peace, progress and economic growth. He is erudite, scholarly and accomplished. This is the first time he has addressed an audience in the City of New York. I am sure you will be pleased to listen to the voice of an Irish official representative, and I now ask you to let him tell us about Ireland, present and future.

(Professor Smiddy’s Speech)

Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen:

I deeply appreciate the very great honour conferred upon me by the Committee of the American Irish Historical Society in asking me to this banquet this evening, and in also asking me to address you on this very happy occasion. I appreciate it especially, as this is the first occasion on which I have spoken in public in the United States, and I am somewhat fearful that some of the ideas that I am going to put before you this evening are of rather a dry character, some of them perhaps a little bit academic, so much so that I think they place me in the category of those dry after-dinner speakers referred to by Mr. Smith (laughter). However, I think you are all benevolent enough to bear patiently with these remarks. They are important, inasmuch as they come right to the kernel of the present difference which is causing us so much regrettable trouble and has resulted in such tragic events in Ireland.

The words “Free State” are translated in the Irish language by the term “Saorstat.” Now, when the declaration was made in 1918 by the First Dail Eireann for Ireland as a Sovereign State, the word “Saorstat” was the Irish name officially adopted as the most appropriate to express the implications of the word “Republic.” “Saorstat” is the only word used since that time by successive Dails, in official documents written in the Irish language, when reference is made to the idea of a Republic. It means “Res Publica” in its original sense, emphasizing the idea of national or common weal.

Now the late Mr. Arthur Griffith (applause), when discussing with Mr. Lloyd George what name he intended or wished to give the new State of Ireland, said that he wished to give it the name “Saorstat.” Mr. Lloyd George asked him what was the meaning of the word. And Mr. Griffith, to try to get as mild a translation for it as possible, said the meaning of it was “Free State.” “Very well,” said Mr. Lloyd George, “we already have one Free State, the Orange Free State, hence I agree to the term ‘Saorstat.'”

Hence we have a continuity of the original name given by the first Dail in the Irish Free State, and we shall see that its implications have been largely realized.

I am going to refer to one of the criticisms against the Treaty and the Constitution that has caused most trouble, and unfortunately most bitterness: the fact that the name of King and Crown plays such an important part in the Treaty and the Constitution. In reality they are merely legal forms, and possess meanings quite different from the original meaning of these words. The Imperial Crown is an institution quite distinct from that of the British Monarchy. The two institutions are blended in the one person, and therefore their fortunes are interlinked. This distinction explains the fact that while Republicanism was recently gaining in Europe and overthrowing thrones, the British Monarchy, on the other hand, seemed to have gained in prestige.

Now, an eminent writer on the subject, Mr. Duncan Hall, an Australian, who wrote a book called “The British Commonwealth,” says:

“The position of the Crown as a great bond uniting a society of Free Republics is, indeed, one of the most remarkable features of modern times.”

The implication of the word “Crown” is simply a bond of unity of co-equal members of a Community of Nations.

The significance of the word “Crown” as only a symbol of unity of a group of free nations was not fully realized even in the year 1917. However, it became prominent in the constitutional developments of the World Peace Conference period. In that period the Prime Ministers of the various Dominions emphasized this point, as also the sovereignty of their countries. Sir Robert Borden, in a memorandum circulated on behalf of the Dominion Prime Ministers to the British Empire Delegation, March 12th, 1919, stated:

“The Crown acts on the advice of different constitutional units within the Empire.”

Again, even in the space of one year, the attitude towards the Governor-General changed. The doctrine of 1918 was that of the Governor-General as Viceroy; while the doctrine of 1919 was that of the King as King of Canada, as King of South Africa, as King of Australia. The King has also acted on a number of occasions in foreign affairs, on the advice of the ministers of the dominions, — not on the advice of the Prime Ministers of Great Britain. The Winnipeg Free Press stated in 1919 that

Cheered in Washington DC: WT Cosgrave arrives in the US capital with Ambassador Timothy Smiddy (left) and William Castle jnr, assistant secretary of state.

“The Crown occupies in the constitutions of all the confederate states virtually the same position and wields in each virtually the same prerogatives.”

Another development of constitutional rights is the control by the Dominions over their foreign affairs. We have, for example, the appointment by the Crown, on the advice and responsibility of Dominion ministers, of Dominion Plenipotentiaries to sign the Peace Treaty in the name of the Crown and on behalf of the Dominions, and the ratification of the Treaty by the Crown on the advice and responsibility of the Dominion Ministries.

The Dominions have power to make tariffs and commercial treaties, immigration agreements and conventions, to deal with merchant shipping, copyrights and shipping rights, naturalization, and the appointment of diplomatic agents. Some people have already said that the Free State is precluded by the Treaty and by the Constitution from appointing diplomatic agents. That is absolutely false. There is nothing in the Treaty and nothing in the Constitution to preclude Ireland from having diplomatic agents. It is purely a matter for arrangement between the Irish Free State and the Government of Great Britain. We already have a precedent in Canada, and it leaves no doubt in the matter. On May, 1920, Mr. Bonar Law made, in the House of Commons, the following statement:

“It has been agreed that His Majesty, on the advice of the Canadian Ministers, shall appoint a Minister Plenipotentiary who shall have charge of Canadian affairs.”

Now, I must not be understood from these remarks as necessarily regarding the monarchial form of government of England as the best, and the Crown as a symbol of unity of independent groups of nations as the ideal. I wish simply to emphasize the idea of the development of sovereignty during recent years in the British Dominions; and who can state that this development is going to cease? Each development of the idea of sovereignty leads inevitably to a similar development in the others. Ireland, as a co-equal member of this Community of Nations, can exercise her influence for the development along lines to suit her own temper, and her own aspirations.

If you compare the form of treaty that Mr. De Valera was willing to accept, you will find really only a difference of words. In fact, Mr. De Valera went further in some respects towards the recognition of the British Empire in being willing formally to agree to pay a contribution to the British King as head of a Group of nations; and Mr. De Valera himself never suggested that Ireland would cease to be a part of the Empire. On a memorable occasion he was willing to accept, for instance, the Cuban status instead of a Canadian status; while, to anyone who would reflect, it is obvious that the latter gives practically a larger measure of sovereignty than the former. For instance, the Platt Amendment reduces the sovereignty of Cuba, insofar as the United States Government reserves the right to retake possession of Cuba, and all agreements with foreign countries made by Cuba must be sanctioned by the United States.

Hence, the development of sovereignty within the British Commonwealth, since the constitution, for instance, of Canada, was ratified, has been most significant; and the implication of that constitution of 1867 has been modified, and expanded, in many vital respects, by the growth of constitutional conventions. The legal power of the Imperial Crown is becoming ever more symbolic, while there has been a continued growth of constitutional rights restricting any outside interference.

Now, this treaty which was entered into between the Irish and the British Plenipotentiaries was submitted to the Second Dail Eireann in January, 1921, and was duly ratified by it. Subsequently an arrangement was effected between the late General Michael Collins (applause) and Mr. De Valera, according to which neither side would contest the seats occupied by the other side at the elections which were to take place, but any individual who wished to go forward for election was not precluded by that agreement. Well, many independent individuals went forward on their own account, especially representatives of Labour, and in nearly all cases these independent representatives got elected and voted for the maintenance of the Irish Free State; so that that election showed that the people of Ireland approved of the Treaty that was entered into between Great Britain and Ireland.

Mr. De Valera on that occasion agreed that that election should be for the twenty-six counties. Therefore, when he accepted that election, he accepted also the going out of existence of the Second Dail; and therefore it is very hard to understand why Mr. De Valera still maintains that the Second Dail has never gone out of existence and that it is at the present moment the Irish Republic.

I find it hard to pass this particular point without referring briefly to the late General Michael Collins. You all know a great deal about the late General Michael Collins as a soldier, and as a general. You know of his heroic deeds during the tragic Black and Tan regime in Ireland. At that time he was the man that steadied the country in moments of despair; he was the man who risked his life over and over again, and risked it so often and in such circumstances that all of us believed that he had a charmed life, and would live to see the Irish Free State prosper and reap the fruits of the freedom that he gave it. But there are not many who know Mr. Collins as an administrator, as a statesman. It was in his capacity as an administrator that I came into intimate contact with the late Michael Collins, especially in the realm of finance and economics. Mr. Michael Collins, during the exciting times in which he lived, notwithstanding the difficulties he was up against, that required immediate attention, steadily kept his mind on what was going on in the country, and started to plan out economic schemes of various kinds which would be slowly realized over a long period of time. He gathered round him for that purpose the most expert Irishmen that he could get; very many of them Irishmen who had reached very distinguished positions in England and elsewhere. He gathered these men around him to advise him as to the best economic policies to adopt in the different spheres of administration. In this respect he showed a very wide vision. He was also a man of wonderful detail. Nothing was too small for his attention. He kept in touch with all the activities of the various departments; informed himself as to how each department was functioning, so much so, that every other Minister and those under each Minister were inspired by his example, and by his enthusiasm. He also had a vision that the Irish Free State, through the power it would exert in the Imperial Conference of the Dominions, and through the power which it would also exert in the United States, would be a means of promoting a real international Comity of Nations founded on ideals of justice and peace.

Now, the present Civil War in Ireland is of a very peculiar character. It is not a territorial civil war; it is more properly a politico-domestic war, where you have the brothers in one family taking different sides, fathers and sons having different views about the status of Ireland. But the consequences of the present civil war are very serious. First of all, the effects in Ireland; second, the effects in the United States. The destruction of property during the last six months in Ireland has been considerable. The claims for this destruction already have reached close on $100,000,000, at least. This means an increase in taxation. It also already has manifested itself in the fact that the budget is not balanced. In 1920, after paying all expenses for running the country, Ireland as a whole paid a surplus to Great Britain of $80,000,000. That surplus at present is converted into a deficit. That deficit is caused purely by the destruction of property, and, naturally, if it continues it means that Ireland has got to meet one of these days a large National Debt.

Smiddy residence in Washington DC

Again, the present strife weakens our ability to enforce to the utmost the clause in the Treaty for the establishment of a Boundary Commission. According to the Treaty a Boundary Commission is to be set up, which Boundary Commission is to allot certain areas in Ulster in accordance with the economic and geographical conditions of these counties. Now, the Northern Parliament has said, that it will not consent to a Boundary Commission. That is largely the result of the present strife in Ireland. Again, it is giving to Ulster a balance of power which may have serious consequences in the future. However, these unfortunate conditions will only delay Ulster’s advent into the Irish Free State, because in the long run it will be to her interest economically to come in to the Free State.

For instance, the two main Ulster banks, that is, the Ulster Bank and the Belfast Bank, draw a very large part of their resources from the deposits of farmers in the south and west of Ireland. Again, these two banks have the power to issue currency, to issue notes, which notes circulate throughout the whole of Ireland. The railway that runs between Dublin and Ulster goes in and out sixteen times on the Ulster frontier. In consequence of this economic unity, Ulster will sooner or later be compelled to come in and join the Free State. (Applause.)

Already there are informal meetings between the members of the Irish Free State government and the members of the Northern Parliament. For instance, in the matter of labour questions, the Minister of Labour of the Irish Free State and the Minister of Labour of the Northern Parliament have met and discussed and arranged certain matters dealing with labour problems.

Well, now, from time to time there will rise up committees to adjust matters of common economic interest.

Take again the banking question. Ireland has got the power, under the Treaty, to establish its own currency and banking system and these banking questions must be discussed between the bankers of Southern Ireland and the bankers of Northern Ireland Likewise, for many economic activities, there will be an increasing number of committees formed. They will naturally grow into one general committee that will adjust all differences of common interests, and there you have the nucleus of a common parliament for the whole of Ireland. It is to be desired that this union will come about as quickly as possible, because Ulster would be of very great assistance to the Free State. The characteristics of the Ulster men as business people are well known to us all. From the economic point of view they would help us while at the same time we would help them in at least an equal measure.

The consequences in America of the civil war m Ireland are also very regrettable and very serious. My own experience is that the present strife in Ireland has rendered many Americans of Irish descent a bit apathetic, and a bit pessimistic about Ireland In that respect we are losing the great advantages and moral influence that we need at this moment from their co-operation and from their action in getting to the fullest possible extent all the advantages that the Treaty with Great Britain gives us. Many of these advantages are implied in the Treaty, and they can be fructified only by putting the Irish Free State in a position of very strong bargaining power with Great Britain.

These regrettable consequences have been begotten as the result of the shadowy differences between the Treaty and the document that would be substituted for it, known as ‘Document No. 2’. But the ground of the opposition by Mr. De Valera and his followers to the Free State has now been shifted, and the emphasis is now given to the immediate realization of a Republic. At the present moment the creation of such a hope in the minds of the Irish people and their kith and km m this country,— of those who are credulous enough through their great zeal to see Ireland a sovereign state now, — is really only a will-o-the-wisp to lead Ireland at the present juncture to its perdition. Then why court this disaster? And if some of you think its consequences uncertain, why risk such well-founded danger when the Treaty and the Constitution put Ireland in a position to reap the advantages of time, which are inevitably on the side of the full sovereignty of the dominions, which we saw is already in process of realization?

If for instance, tomorrow the Republic in Ireland got into power, what then? They would be faced immediately with the British Government, and the British Government is not going to allow Ireland at present to form a Republic by default. It means that England will enter again into Ireland, and she will enter with a moral power she had not when she put the Black and Tans upon us. She will enter in with the concurrence of most European nations, and the protests from them will be very few.

As a matter of fact, before the truce was entered into that led to the Treaty, the condition of Ireland was very pitiful, and Ireland could not hold out against the British forces for over two months. That is the most that Ireland could have held out against Great Britain. That fact was very well known, and has been referred to quite frequently. If the idea, then, of Irish Unity is seriously desired by Mr. De Valera as an asset in obtaining, even now, a Republic, why render it impossible of attainment by force of arms against the Free State? The natural and statesmanlike course would be to adopt the constitutional one to abide by the forthcoming election, when the new register will be drawn up, giving thereby every man and woman over twenty-one years of age a vote. Here we shall have all the requirements for the real expression of the will of the people.

It is a futile and impossible condition to lay down for such an election that Great Britain should withdraw the threat of war in the event of Ireland declaring for a Republic. It is then evidently most unreasonable to lay the blame for the non-fulfilment of this requirement on the government of the Free State. The Free State has to accept the facts of the situation and cannot possibly extract such a condition from the British Government. The signatories of the Treaty have already obtained the last ounce of liberty which was possible, and which was obvious to anyone who was in close touch with the Plenipotentiaries in London. It is up to Mr. De Valera and his followers to throw their lot in with the Free State and help to secure for Ireland, to the utmost, the liberties which are expressed and implied in the Treaty and the Constitution; to avail themselves of the possibility of the development of sovereignty which is at present at work in the various dominions. And, in fact, this development consists in the abrogation of legal powers which are not exercised— more properly, legal fictions,— and in the realization of constitutional rights growing out of the economic and political conditions, and the growing consciousness among the Dominions of full national sovereignty.

“What man can set bounds to the onward march of a nation:” and say, “Thus far and no farther?”

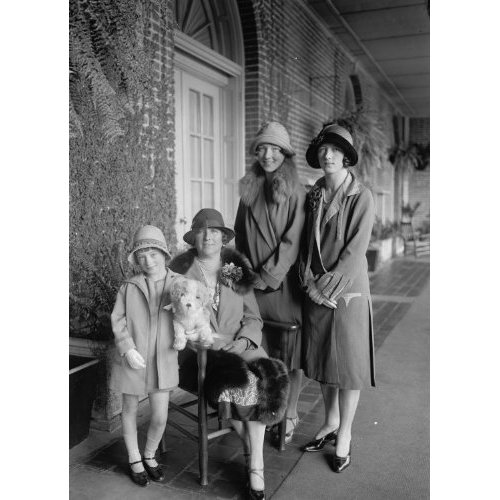

Ethna, Pearl, Cecil and their Mother Mrs. Timothy A. Smiddy 1926

The Irish Free State at present has many of the elements of sovereignty, and it is only a matter of time when any deficiencies that exist therein will be made up for. Hence, Mr. Cosgrave and his Government are not the aggressors in this strife, but are in a great crisis acting as the bulwark of Irish freedom and preserving the hard-fought-for liberties obtained under the Treaty.

Under the Treaty we have got full power over our finances, and our economic development. We can make commercial treaties with any countries we wish. We can put up tariffs, if we wish, against Great Britain herself. Now, this concession was one of those which the British Plenipotentiaries most reluctantly conceded. During the first weeks of the negotiations Lloyd George consented to allow Ireland to protect, by tariffs, certain industries of national importance, and consequently to enable us, or at least to allow us to put up tariffs also against goods which were imported into the country at a cheap rate in consequence of foreign exchange. Later on, about two weeks after, he withdrew the latter concession, and agreed only to have tariffs put up for certain industries of national importance. Later on, about ten days before the Treaty was signed, the British Plenipotentiaries laid down that there must be Free Trade between England and Ireland,— in other words, that we were to be deprived of the power to put up tariffs if we saw fit, against England. Well, if that power was not given to us, the Treaty, in substance, to my mind, would not be worth a great deal. However, at the last half-hour of the negotiations, early on Tuesday morning, Lloyd George waived his objections and allowed Ireland to have full power to put up tariffs if she so desired, against England itself.

Some of you may not have any idea of the extent to which Ireland is an exporting country and an importing country. In 1920 the exports from Ireland reached $1,000,000,000, and the imports reached practically the same; so the total foreign trade of Ireland reached $2,000,000,000. Now, one peculiar feature of this foreign trade is that almost ninety per cent of it is direct with England and Scotland. Therefore, we are dependent mainly for our markets on England, which is not the best possible method for the distribution of our exports. It is much more ideal, if it can be accomplished, to diversify our trade, develop our trade with other European countries, and especially to develop a trade with the United States. Our trade with the United States is not as great as it might be. It is principally on the side of exports from the United States to Ireland. For instance, last year the value of American exports to Ireland reached $45,000,000, whereas the exports from Ireland to the United States reached somewhere about $12,000,000. Hence, then, one of our problems will be to find many of the markets for our exports other than Great Britain.

Then the social advantages of diversified trade, the educational advantages of diversified trade, are to be considered. They bring people together; travellers will come from Ireland to America; from France to Ireland; from Ireland to France; from America to Ireland, etc., and such travellers will bring ideas of culture and ideas of scientific and other knowledge.

Now, I ask you to have patience and confidence in Ireland, and to seek to instil into the minds of those with whom you come in contact a hope for Ireland and a trust in Ireland.

Now, the present strife in Ireland is no exception to history. It is pointed to sometimes, and quite frequently, as abnormal, — that the Irish always are fighting among themselves. Well, really, a large measure of liberty in most countries has been associated with civil war or strife of some kind. The five years that followed the Treaty between Great Britain and the United States in, 1783, — I think it was, — those five years were the critical five years, and the most critical five years in American history. The troubles and difficulties that arose, and the strife that you had, I think, were at least as great perhaps greater than — those that we have at the present moment in Ireland. Then again you had a civil war, with great numbers who sacrificed themselves for the idea of federal unity. So, we are simply paying the price for our liberty at the present moment by this strife.

I take advantage of this occasion to thank the American people, and especially the officials of the various departments in Washington, for the great help that they have given us already, and for the manifestations of practical help which they intend to give us in the future. I have been in Washington, practically speaking, since last April, and I have had occasion to interview the heads of most of the departments and to investigate their methods of procedure, their methods of business and internal organization, and each and every one of them was most anxious to give practical help. They were willing to put their offices at my disposal, or at the disposal of other Irishmen who came across to study. The organization of the federal government gave us their offices, placed their staffs at our disposal, and gave us every attention and assistance at their command, gathering for us all the documents and books, so that we have a great idea of the organization of these various departments. Only last week Sir Horace Plunkett, a Senator of the Irish Free State, has carried on in the Bureau of Agriculture a most important investigation, in which he was helped to a very large extent by the Secretary of that Department, who put at his disposal a staff to enable him to make his researches.

Then, again, the present Irish Free State owes its existence largely to the American people. The financial support given to the Irish Free State by the American people, the political organizations which the American people formed to push forward the Irish cause, these were really, to my mind, conditions precedent to the possibility of an Irish Free State, and without them we could not possibly have got it. Here, again, the Irish people are beholden to the people of the United States, especially to those of Irish descent.

I ask you then to use your influence on behalf of the Irish Free State, and I ask you who do not agree with us, to reflect, study the Treaty and the Constitution, and the tendencies in the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, which are making towards full sovereignty. In any event, I ask you to preach the doctrines of constitutional methods — it does not matter what your ideas may be on the subject — to secure a dignified opposition — if any there is to be — in this country, based upon facts and based upon arguments.

Ireland has suffered for long; many have died for her — some on the altar of abstractions. Hence, finally I pray you, by your influence to make “living for and enjoying Ireland” be the ideal to realize at present. (Applause.)