Death Of Michael Collins

http://chris-dalton.com/2008/07/05/

first-hand-account-of-the-death of michael collins partone/- comments

BLOG

My brother and I like to surprise each other with hitherto undiscovered family artifacts and memorabilia. I’ve written a little before about the extraordinary sailing by four young Irishmen in the summer 1950 of the 36-foot gaff-rigged yacht the Ituna from Dublin to New York. My father being a member of that crew, architecture students with none too much sailing experience between them. Skip back another Irish generation and there are also tales to tell. Both my grandfather and great-Uncle were intimately involved in the Irish War of Independence (1917-1921) and ensuing Civil War, and both served alongside Michael Collins, who famously outwitted the mighty British military intelligence machine and infamously died in a minor Civil War skirmish in the countryside near his home town in 1922. Great Uncle Emmet Dalton, an experienced army officer who had fought for and been decorated by the British in the Great War, had become one of Collins’ closest and most loyal military commanders, and it was he who accompanied the ‘Big Fellow’ on the tour of the south. This, and a number of first-hand accounts of the ambush, have been published in various books and websites. But I was amazed when my brother showed up with Emmet’s own typewritten version of the events of that day, set down just three months later. The account is preceded by a handwritten note, which I am attaching. I know it’s not strictly part of the remit of this blog, but I figure enough of you will have heard of the story or seen the biopic of Collins’ life for it to have its own historical interest.

The cover note reads:

“The death of Micheal O’Coileain.

I dedicate this, my first little work to my youngest brother Pat, hoping that when he witnesses the improvements in Ireland’s welfare, he will occasionally allow his mind to dwell upon the memory of my dearest friend.

J Emmet Dalton

23rd Nov. 1922″

The script that follows this reads:

“The war which had been forced on the people of Ireland by the Mutineers from the I.R.A. had been in progress for two months, and Cork had been captured by forces under my Command. We had been in occupation two weeks when upon the evening of the 20th of August I received an unexpected visit from General Michael Collins, Commander-in-Chief of the Army. He had been on a visit to General O’Duffy at Limerick, and, with an escort of three Officers, twelve men and a ‘Whippet’ armoured car, he had motored from Limerick to Cork. Most of the route he had taken was in occupation of bands of Irregulars and had not up to then been entered by Army Troops.

He had two objects in visiting my Area, the first being to inspect the Military Organisation in the Area and to appreciate the difficulties of the Military problem with a view to giving his advice, and in order that he might more easily render the necessary assistance from General Headquarters, having seen for himself the position. His second object was of a civil nature. In his capacity as Chairman of the Provisional Government, and Minister of Finance, he was anxious to make every effort to recover some of the thousands of pounds that had been extorted from Banks by the Irregulars prior to their retreat from the city. The stolen money was Excise duties belonging to the Customs and Excise Department, and it amounted to £120,000. They obtained the money by capturing the Official Collector, retaining him, and under threat of force, making him sign the cheques which, of course, the Banks honoured and paid.

Upon his arrival in Cork City at 8.30 P.M. on Sunday the 20th August, General Collins complimented himself and my Officers upon the success of our expedition. He then arranged interviews with his relatives and friends in the City. On the morning of the 21st, he, accompanied by me, inspected various Military Posts in the city, after which he interviewed several prominent citizens, including the Managers of the Various Banks, in connection with the stolen money. In the afternoon we motored to Macroom where he inspected the Garrison and the Military posts. Then, owing to the fact that the escort armoured car was not running satisfactorily we found it necessary to return to Cork. He spent two hours in interviewing his friends in the city before retiring he arranged to devote the entire following day to a tour of inspection of the Command Area, as far as Bantry.

At 6.15 A.M. on the morning of the 22nd our little party left my Headquarters (The Imperial Hotel) to commence our tour. The convoy consisted of, and advance Motor Cyclist Scout Officer, followed by a party of two Officers, eight riflemen and two machine gunners with one Lewis Machine-gun, mounted on an open Crossley Tender. The next car was an eight-cylinder touring car with a light racing body, this car had two drivers in front, and in the back were General Collins and myself. Our first halt was Macroom, but because of the extraordinary amount of bridge destruction and road obstruction that had been participated in by our retreating enemy, it was necessary for us to take a roundabout route, entailing much delay, consequently we made only a hasty inspection, picked up a guide and headed for Bandon. Here General Collins spent some time discussing the position with the officers of the Garrison before proceeding to Clonakilty. About three miles from Clonakilty we found the road blocked with felled trees. We spent about half an hour clearing the road under the guidance and instruction of, and with the assistance of, General Collins himself. He used a cross-cut saw and a heavy axe with tremendous energy and satisfactory results.

Having cleared the road we proceeded into the town of Clonakilty, which is the home town of General Collins. He interviewed the Garrison Officer and had conversations with many of his friends, all of whom were delighted to meet him. We had lunch in a friend’s house in the town before setting out for Rosscarbery. About three miles from Clonakilty we halted at a hamlet in the vicinity of Sams Cross, which the home of the Collins’. Here the General was welcomed by his brother Sean and several of his cousins. We spent about a half an hour with these friends discussing domestic affairs, before we proceeded on our journey. A peculiar circumstance of this journey was, that practically every relative the General had was encountered and spoken to.

Having reached Rosscarbery we consulted with the Officer in charge of the Garrison before proceeding to Skibbereen where again, in the ordinary Military way, General Collins consulted with the Garrison Officers, listening to their complaints, giving them advice and assuring them on the further co-operation from the Army Authorities.

Owing to the fact that it was now about 5 o’clock it was decided not to proceed to Bantry, but to return to Cork by the road which we had taken. We passed through the towns of Rosscarbery and Clonakilty, then to Bandon where we delayed for half an hour, whilst the General was conversing with several of his friends and two of his cousins who had just returned to the town with the Flying Column. One of the Officers who came from the locality remarked to the Commander-in-Chief that our escort was very small, and that the country we would pass through was much frequented by bands of Irregulars. His remark was greeted with a confident smile and General Collins said “Where you can go, we can also go.” However, it was soon obvious (to me) that he had carefully noted the remark because he said to me when we were starting off “If we run into an ambush along the way we will stand and fight them.” Just outside the town of Bandon he pointed out to me several farmhouses which he told me were used by the lads in the old days. He mentioned to me the home of one particular friend of his own, remarking “It is too bad he is on the other side now because he is a damned good soldier.” Then he said “Don’t suppose I will be ambushed in my own County.”

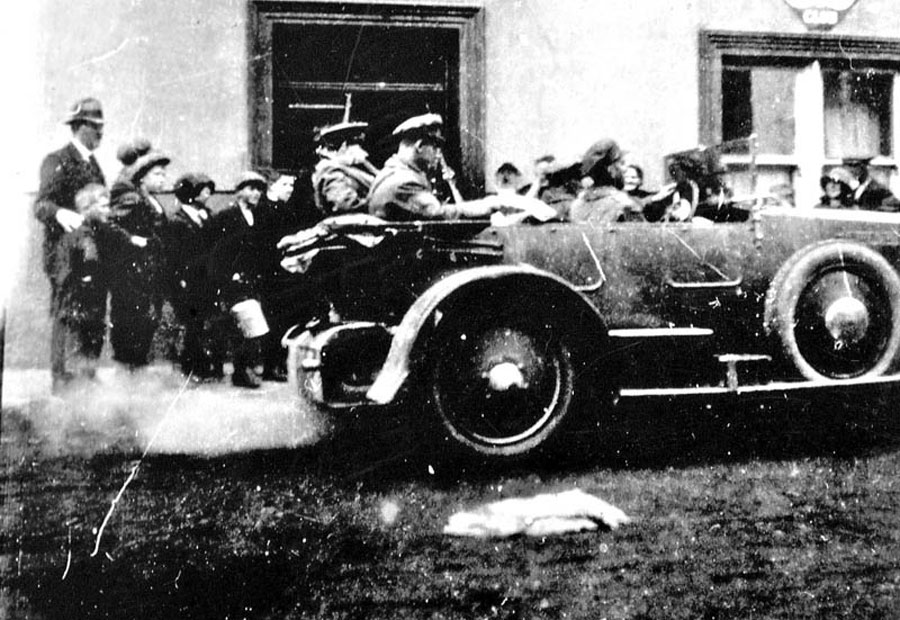

I will add the concluding part of Emmet’s account in the next instalment. The picture of the car is Emmet and Michael Collins at the back of the convoy.

Back from Dublin at the weekend, where I ran a workshop for one of the MBA intakes to focus them on writing their big Stage Two assignment, the Integrated Management Project. It was a pleasure to be there and see our Irish partner, the Irish Management Institute (IMI), which is housed in a concrete and glass building that one suspects was recognisably of its time when built and which may well be considered a great example of that school of architecture in the future, but which hasn’t quite weathered its environment yet. Like Henley in the UK, the IMI is a free-standing and independent venture in talks with a university (Cork) for merger. On the way back to the UK I had some time on a lovely September afternoon to walk around the city centre. With the second vote on the Lisbon Treaty coming up in a couple of weeks, there was hardly a lamppost in the town that did not have at least one or two posters campaigning “No” or “Yes”. It appeared to me that the yes vote was slightly more dominant, and this appears to be the opinion of those I spoke to as well. The initial no was delivered on the back of some slick and impassioned campaigning by Libertas (now more or less absent from the debate) and a coalition of “fundamentalist Catholic” (a term to send shivers down the spine) groups. The latter are still vocal but the argument seems to have swung another way following the economic collapse of the Celtic Tiger.

The other thing that everyone there is talking about is NAMA (National Asset Management Agency), which is the Irish Government’s plan to deal with the credit crunch in property by buying up the portfolios of the major Irish Banks. The controversy revolves, of course, around the price of this since no-one wants to compensate the banks and developers for the speculative property boom that Ireland went through. On the way through the city centre I picked up a copy of Meda Ryans’ book “the day Michael Collins was shot”, which details the week or so around the ambush and which has quite a lot of testimony from Emmet Dalton. Then, as I was crossing the Liffey on O’Connell bridge I was in time to see the 200 or so swimmers in the 90th annual Liffey swim make their way against the tide to the finish line. Quite a crowd of onlookers formed to see them go by and a couple of German tourists asked me “how long is the swim?” Since one of our MBA programme members that I had done the workshop with that morning works in the Dublin Fire Brigade, and was one of the organisers of the day (providing the decontamination showers at the end) I was able to tell them that is was over 2km. “Ah, not so long” was the reply, at which I felt the ancestral need to defend the grandness of the task. “It is against the tide,” I added, staring him down until and forcing a grudging semblance of being impressed onto his face.

Following the earlier post on this topic, here I reproduce the words of my Great Uncle Emmet, Major General in the Irish Free State army at the time of the creation of the State of Eire in the 1920s. Emmet was with Collins on August 22nd 1922 and soon after wrote his own short account of the events of those days. His typewritten manuscript, the final page of which is shown in the picture here, has been used as source material in several accounts of those times, but since it is a rare opportunity where world events collide with family history, I take the liberty of including it in this blog.

There is another, subtle and ulterior, motive related to the development of my own doctoral research into the effects in Management Education of Critical Reflection using family-of-origin input. In this instance, for Emmet and also his younger brother Charlie (my grandfather) the extraordinary events of their youth created ripples that are still felt in the family several generations later. So, back to Emmet’s story:

“It was now about a quarter past seven and the light was failing. We proceeded along the open road on our way to Macroom. Our Motor Cyclist Scout was about 50 yards in front of the Crossley Tender which we followed at the same interval in the touring car, and close behind us came the armoured car. We had just reached a part of the road which was covered by hills on all sides. The road itself was flat and open; on the right we were flanked by steep hills on the left of the road there was a small 2 ft bank of earth skirting the road. Beyond this there was a marshy field bounded by a small stream and covered by another steep hill. About half way up this hill there was a road running parallel to the one we were on but screened from view by a wall, and a number of trees and bushes. We had just turned a wide corner on the road when a heavy fusillade of machine gun and rifle fire swept the road in front of us and behind us, shattering the wind-screen of our car. I shouted to the Driver “Drive like Hell” but the Commander-in-Chief placing his hand on his shoulder said “Stop. Jump out, we will fight them.” We jumped from the car and took what cover we could behind the little mud bank on the left side of the road, it appeared the greatest volume of fire was coming from the concealed roadway on our left hand side. The armoured car backed up the road and opened a heavy machine gun fire at the Ambushers. General Collins and I were lying within arm’s length of each other. Another Officer who had been on the back of the armoured car, together with our two drivers, was several yards further down the road to my right.

General Collins, I, and the Officer who was near us opened up fire on our seldom visible enemies, with rifles. About fifty or sixty yards further down the road and around a bend we could hear that our machine-gunners and riflemen were heavily engaged. We continued this fire-fight for about twenty minutes without suffering any casualties, when a lull in the enemy’s fire became noticeable. General Collins jumped to his feet and walked over behind the armoured car, obviously to obtain a better view of our enemy’s position. He remained there firing occasional shots, using the car as cover. Suddenly I hear him shout “There they are running up the road.” I immediately concentrated on two figures that came in view on the opposite road. When I next turned round the Commander-in-Chief had left the car position and had run about fifteen yards back up the road, dropped into the prone firing position and opened up on our retreating enemies. A few minutes had elapsed when the Officer in Charge of our escort came running up the road under fire, he dropped into position beside me and said “They have retreated from in front of us and the obstacle is removed; where is the ‘Big Fella’?” I said he is all right – he has gone a few yards up the road, I hear him firing away.” Then I heard a cry “Emmet, I am hit.” The two of us rushed to the spot, fear clutching our hearts. We found our beloved Chief (and friend) lying – motionless in a firing position, firmly gripping his rifle across which his read was resting.

There was a gaping wound at the base of his skull behind his right ear. We immediately saw that he was almost beyond human aid; he did not speak. The enemy must have observed that something had occurred that had caused a cessation in our fire because they intensified theirs. O’Connell knelt beside the dying but conscious Chief, whose eyes were open and normal, and he whispered into his ear the words of the Act of Contrition; he was rewarded by a slight pressure of the hand. Meanwhile I knelt beside them and kept up bursts of rapid fire, which I continued whilst O’Connell dragged the Chief across the road and behind the armoured car. Then with my heart torn with sorrow and dispair I ran to his side. I gently raised his head on my knee and tried to bandage his wound, but owing to the size of the wound this proved difficult and I had not completed my sorrowful task when his eyes quietly closed and the cold pallor of death covered his face. How can I describe the feelings that were then mine, kneeling in the mud of a country road not 12 miles from Clonakilty with the still bleeding head of the Idol of Ireland resting in my arms. My heart was broken my mind was numbed, I was all unconscious of the bullets which still whistled and ripped the ground beside me. I think that the weight of the blow would have caused me the loss of reason had I not observed the tearstained face of O’Connell distorted with anguish.

We paused for a moment in silent prayer and then noting that the fire of our enemies had greatly abated and that they had practically all retreated, we two, with the assistance of a third Officer who had come on the scene, endeavoured to lift the body on to the back of the armoured car. It was then that we suffered our second casualty, the recently arrived Officer (Motorcyclist Lt John J. Smith) being shot in the neck. He, however, remained on his feet and helped us to carry our precious burden around a turn in the road under the cover of the armoured car. Having transferred the body of our Chief to the touring car where I sat with his head resting on my shoulder, our sorrowful little party set out for Cork.

The darkness of night had closed over us like a shroud. We were silent, thinking with heavy hearts of the terrible blow we would soon deliver to our unfortunate country and to the Irish people throughout the world. We had left Cork City that morning – confident and contented – intent on improving the machinery of the only possible representation of the Government that could bring peace to a sorely-tried long-suffering people. We had with us the man to whom the people of Ireland had entrusted their welfare; the man who had risked his life so often in their interest; the main who was loved by his friends and respected by his enemies. Our day had been a succession of triumphs. And now, at its close, like a bolt from the sky, fight had been forced upon us. We had fought with success – but our victory was nothing in the immensity of our loss. He was gone.

We had suffered the loss of a generation – we lost what the contrition and remorse of a nation cannot restore. The country had lost its leader – the people had lost their Idol – the Army its Chief …. and his intimate friends had lost the “Big Fella.” What an end for Michael Collins. Shot dead in an Ambush. Killed by his own Countrymen in his own Country – near his own home. Killed by the mean he fought and suffered with – the men he had been so proud of – and in the country he had loved to call his birthplace.

* * * * * * * * *

We reached the City. It was midnight, still, dark and silent – a fitting tribute to our little Procession. The thought struck me that those poor people had gone peacefully their nightly rest, all unconscious of the calamity that had befallen them. Some, perhaps, with cherished remembrance of the strong smiling face they had yesterday cheered in the streets. To myself I thought, what an awakening tomorrow will bring – what bitter sorrow will overwhelm this poor city ere the sun has reached its zenith. Michael Collins was dead.