Béal-na-mBláth

Béal na mBláth

Notes from the Shadow of BealnaBlath — by Colm ConnollySome of those leaders had already been captured and were being held in Maryborough Gaol (now Portlaoise Prison). Collins spent an hour talking to them (group included Tom Malone aka Forde of the Western Command IRA) but, obviously unsuccessfully, He left in a vexed mood for County Limerick. He was suffering from a heavy cold and a kidney infection. He was in constant pain and discomfort and had to stop frequently on the journey. He was edgy, too. Watching his men removing a bridge obstruction near Kilmallock, a local man took the opportunity to take a souvenir snapshot of the famous Michael Collins. He approached quietly and the click of the camera made Collins reach instinctively for his revolver.

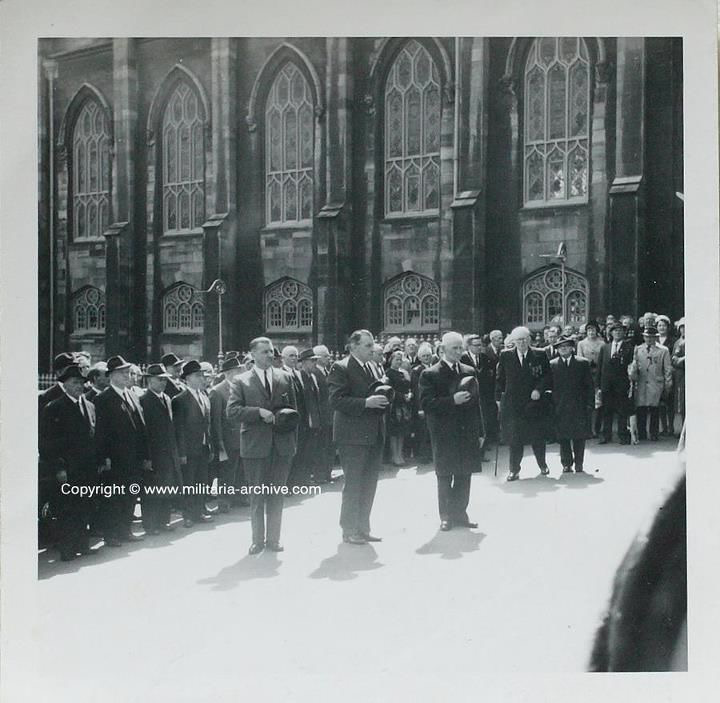

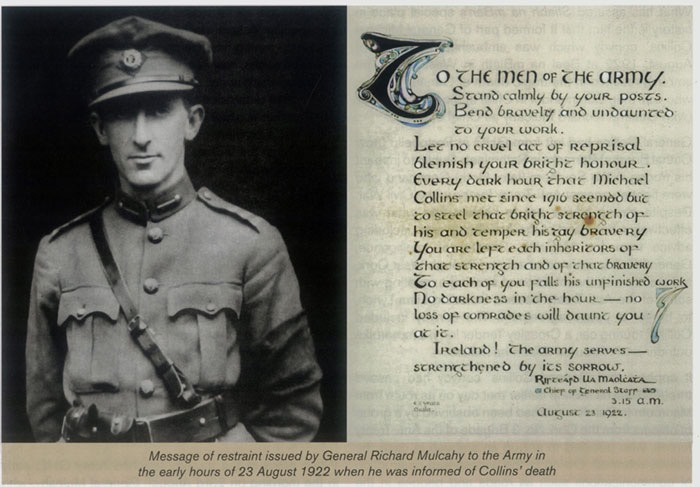

E company 2nd Battalion Old IRA. Seán Lemass, Taoiseach of Ireland (and former member of Michael Collins Squad) Capt Frank Thornton, President 2nd Batallion, Vinny Byrne Chairman Dublin Brigade, Dublin Castle comemoration mass for Michael Collins.

After inspecting the Free State garrison in Newcastlewest, he travelled southeast to Mallow in County Cork and then, that evening, to the Imperial Hotel in Cork where Emmet Dalton had set up his headquarters after the capture of the city. ‘l was concerned to see him there’, Dalton recalled.’l knew how boyish he was, and the warmth and extent of his heart. He had a devout love for the people in Cork. I told him he was taking an unnecessary risk being there, and he said, jocosely, “Surely, they won’t shoot me in my own county?”‘

The following day, Collins travelled some 50 kilometres (30 miles) with Dalton to Macroom, where he had some secret talks with an influential neutral IRA officers (believed to be Florry O’Donaghue or/and Sean Hegarty, both men tried with might and main to stop the Civil War in Cork). That afternoon, he made the last entry in his personal diary, ‘The people here want no compromise with the Irregulars . . . . Civil administration urgent everywhere in the south. The people are splendid,. Back home in County Longford, Kitty Kiernan was extremely concerned about his health and safety and told him so. In the last letter he ever wrote to her, he explained, ‘Kitty you won’t be cross with me for the way I go around, and lf I were to do anything else it wouldn’t be me and I really couldn’t stand it. Somehow I feel that the way I go on is better. Please, please don’t worry’.

One of those who met Collins in Cork City was his nephew, Sean Collins-Powell, then a quartermaster sergeant in the Free State army. He and his mother met Collins outside the Imperial Hotel and went inside for tea. Two young soldiers were sitting side- by-side in the foyer, leaning up against each other, half asleep but supposedly on guard duty. Collins banged their heads together and walked on.

‘He was a bit tired at that meeting, Collins-Powell told the author. ‘Of course, he had a very severe cold, bordering on pleurisy, but he was in reasonably good form. He was a very serious fellow and didn’t waste time talking about himself.’ At 6.15 on the morning of 22 August, Collins and Dalton set off from the Imperial Hotel. The convoy consisted of a motorcycle scout, a lorry carrying eight riflemen, two Lewis machine-gunners and rwo officers. Behind the lorry, Collins and Dalton sat in the back of a yellow, open-topped touring car, a Leyland Thomas, loaned to Collins by a well-wisher. The driving was shared by two soldiers. Bringing up the rear of the convoy was the ‘Slievenamon’, a Rolls Royce Whippet armoured car. This carried another officer and four men, including the operator of a Vickers medium machine-gun in its turret (A total of 18 soldiers). This escort was most inadequate for a commander-in-chief in territory teeming with lrregulars.

On this day, the convoy travelled again to Macroom to resume the talks with neutral officers begun by Collins the previous day. After that, the convoy travelled to Bandon via the tiny crossroads village of Bealnablath . Unknown to Collins, senior Irregular divisional and brigade officers had gathered in a farmhouse overlooking the village for a war council. The officer-in-charge was Brigade Commander Tom Hales (who had been captured, tortured and court-martialled by the British in 1920). When Hales was told about the Collins convoy, he immediately planned an ambush in case The Big Fellow should return from Bandon by that route. A beer bottle collection cart was commandeered and placed across the road, 750 metres (820 yards) on the Bandon side of Bealanblath crossroads.

In front of this, a 3O-millimetre-long (12-inch) mine, containing 3 kilograms (7 pounds) of explosive, was buried beneath the surface of the dirt road and connected to a detonating plunger on higher ground. Twenty-two riflemen were placed in position over-looking the road to await a possible return of the Free State convoy. Also unknown to Collins, Eamon de Valera had stayed in a farmhouse close to the village the previous night, and had passed through the crossroads just half an hour after the convoy had first reached Bealnablath. De Valera was also opposed to the Civil War, but the Irregulars’ Commander-in-Chief, Liam Lynch, was reluctant to cease hostilities and, so, told his officers not to encourage de Valera in his efforts. Despite persistent rumour and gossip, there is no evidence to support the claim that de Valera was involved in the planning of the ambush then being laid for his former friend and comrade (deValera left the area for Ballyvourney at 2pm).

Collins, meanwhile, had reached Bandon, travelled on to Clonakilty for lunch, then to Roscarberry, and onwards to Sam’s Cross for a meeting with his relatives. Collins told a local officer that he was ‘going to put an end to this bloody war’. At Skibbereen, he had more talks and left there at five o’clock in the afternoon to return to Bandon for tea. At Bandon, Collins had a detailed briefing from the local Free State commander, Major-General Sean Hales. Thirteen kilometres (8 miles) away at Bealnabliith, Hales’ brother, Tom, fighting on the other side, was waiting for Collins to re-appear. After tea at Lees Hotel (now The Munster Arms), Collins and his convoy set off for Cork via Bealnablath. He had less than half-an-hour to live. In Bealnablath, Tom Hales had sent most of his ambush party back to Longs public house at the cross-roads, convinced by the lateness of the hour that Collins had taken another route to Cork City. With six or seven men, he began the task of removing the mine and barricade. A look-out, was posted in a lane overlooking the main road in case any Free State patrols should appear.

The Collins convoy reached the area just after seven o’clock, 15 minutes before sunset. A drizzle had begun to fall, and a mist drifted across distant fields. Collins, still suffering from his severe cold, huddled into the collar of his greatcoat. The driver and co-driver noticed that he and Dalton had lifted their rifles from the floor and now held them between their knees as they reached the gently curving road into the Bealnablath valley. The look-out in the overlooking lane had heard the engines of the vehicles in the convoy but was unsure about their identity until the motorcycle scout, Lieutenant Jeersey’ Smith, rounded the bend. The look-out fired some shots at the convoy, both as a warning to his colleagues at the barricade and to alarm the convoy.

Dalton yelled at the driver of the touring car: ‘Drive like hell’. But Collins leaned forward and put his hand on the driver’s shoulder. ‘No, stop, and we’ll fight them’, he countermanded.

All four men jumped from the car and took up firing positions behind the low bank bordering the road on the laneway side. Smith had, in the meantime, raced up the road on his motorcycle, followed by the lorry. At the barricade, the men fired at him as they retreated up into the lane. A bullet hit the handlebars of the motorcycle, injuring Smith’s He turned the machine around and abandoned it in the ditch, then waved warnings to the lorry, which just arrived. The Lewis gunners opened fire on retreating Irregulars while the remainder of the soldiers jumped from the lorry and divided into two sections. The first section ran to the barricade to move it aside while the second section gave them cover-fire. The Irregulars ran along the overlooking lane in a series of sprints, firing at the men below, and then diving again for cover. They were under constant firefrom the Lewis and rifles.

After a few minutes, the Free State men moved up the lane, pushing the Irregulars toward Collins and Dalton at the other end of the skirmish area. At that spot, about 450 metres (490 yards) distant, the armoured car reversed a little to get into a better firing position with its Vickers machine gun. The Irregulars said later the bullets of the machine gun clipped the bushes above their heads as they lay flat in the lane between sprints.

Lieutenant Smith and Commandant Sean O’Connell, the officer in charge of the convoy, made their way back along the road to inform Collins and Dalton that the road had been cleared should they wish to proceed. On a sloping hillside to the right of the Free State men nearest the original barricade position, three separate and unconnected groups of Irregulars had joined the battle. The first was led by Mike Donoghue of Glenflesk, County Kerry, and was making its way home after losing Cork City. Unaware of the ambush plan, the group was drawn to the hillside by the sound of gunshots. Another two Irregulars also heard the shooting and made their way to the scene. The original ambush riflemen, who had been at Long’s public house, returned to help their colleagues. At the Bandon end of the convoy, where Collins and Dalton had been firing side by side, another group of Irregulars, on its way home to County Waterford, was also drawn in. All this happened in the l7 minutes that had passed since the first shot fired by the lookout.

By now, Michael Collins was dead. The armoured car’s machine gun had jammed several times. An inexperienced officer had made a mess of loading an ammunition belt and this caused repeated stoppages. In one of these lulls, the pinned down Irregulars took the chance to move further along the lane. Collins saw their movement and left Dalton and the protection of the roadside bank and moved around the bend to fire from the cover of the armoured car. When the Irregulars ran again, he moved from the armoured car to the centre of road. Standing upright, he fired a few more shots. Up in the lane, Denis O’Neill, more commonly known as ‘Sonny Neill’, was covering his companions. He could not resist the foolhardy and reckless standing target. He aimed his Lee Enfield rifle and fired. The bullet entered the front of Collins ‘head on the hairline, passed through his brain and exited explosively behind his right ear. He fell face down on the road, still gripping his rifle.

Firing from the lane had now stopped. The Irregulars had escaped. Dalton, O’Connell and Smith rounded the bend to seek out Collins. They found The Big Fellow ‘with a huge gaping wound at the base of the skull’ and beyond human help. Dalton lifted Collns ‘head and tried to apply a field dressing to the ugly wound. O’Connell whispered an Act of Contrition into Collins’ ear. The firing by the Irregulars, which had abated momentarily, now resumed. A bullet went cleanly through Smith’s neck. There were no casualties on the Irregulars’ side throughout the skirmish. Collins’ body was lifted into the touring car, his head resting on Dalton’s shoulder, and resumed its journey to Cork City. Because of blown bridges and blocked roads, the sorrowful trip took several hours and the convoy did not reach Cork until the early hours of the morning. The body was laid out in a small, top-corner room of Shanakiel Hospital which had been taken over by Free State soldiers after the capture of the city. Dalton sent a telegram to Army headquarters in Dublin advising that’commander-in-chief shot dead in ambush’.

Liam Lynch, Chief of Staff of the IRA, who would himself die in the Civil War, complimented his colleagues in the lst Southern Division on the action at Bealnablath, but added, ‘Nothing could bring home more forcefully the awful, unfortunate national situation at present than the fact that it has become necessary for Irishmen and former comrades to shoot such men as M. Collins’.

When news of the death reached Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, a thousand IRA prisoners spontaneously knelt and recited the rosary for the soul of Michael Collins.

The uniformed body of Michael Collins was brought to Dublin by ship. It was embalmed by Dr Oliver St John Gogarty. He confirmed afterwards that there were two wounds caused by the fatal bullet entry and exit. The body was first laid out in the chapel of the old St Vincent’s Hospital where Sir John Lavery captured the sombre scene on canvas. His wife, Hazel, spent some time standing beside the tricolour-draped body and then left, weeping.

Tens of thousands of men, women and children queued to pay their last respects to Michael Collins as he lay in state in the City Hall beside Dublin Castle. Amongst this who filed past the open Coffin were many British soldiers, his former enemies, wearing black armbands on their uniforms. Even more people lined the route to Glasnevin on Monday 28th August, When the coffin carried on a gun carriage pulled by four Black Horses and escorted by thousands of Free State soldiers made it way slowly to Glasnevin cemetery.

In one of her last letters to Collins Kitty Kiernan had written: ‘l was terrified that you would take all kinds of risks and how I wished to be near you so that I could put my arms tightly around your neck and that nothing could happen to you. I wouldn’t be a bit afraid when I’d be beside you, and if you were killed I’d be dying with you and that would be great and far better than if I were left alone behind. I’d be very much alone if you were gone. Nothing could change that, and all last week and this I’ve realized it and that’s what makes it so hard’.

Hundreds of wreaths were carried on military cars draped in black crepe that followed the gun carriage through the silent streets, but only one floral tribute was permitted on the flag-covered coffin – a single white peace lily. It was from Kitty Kiernan.